OPEN HOURS:

Tuesday - Saturday 11AM - 6PM

Close on Sunday, Monday and Pubilc Holidays

For more information: info@sac.gallery

(English is below)

หลายครั้งที่ “สามจังหวัดชายแดนภาคใต้” มักถูกนำเสนอพร้อมกับคำว่า “ความรุนแรง” ที่ติดเหมือนเงาตามตัวเสมอ แต่หากมองให้ลึกและพยายามทำความเข้าใจจะพบว่า พื้นที่ปลายสุดของด้ามขวานนี้ คือแหล่งรวมของพหุวัฒนธรรมอันหลากหลายและรุ่มรวยไปด้วยอัตลักษณ์เฉพาะ

ปรัชญ์ พิมานแมน เป็นหนึ่งในศิลปินจากพื้นที่ชายแดนภาคใต้ ผู้สร้างสรรค์ผลงานอันเกี่ยวโยงกับผืนดินเกิดของบรรพบุรุษ ผลงานชิ้นต่างๆ ที่ผ่านมาของเขาซึมซับและถ่ายทอดความเป็นมลายูในหลายแง่มุมอย่างลุ่มลึก ผสานมุมมองจาก “คนใน” กับ “คนนอก” อย่างน่าสนใจ

ทั้งของคนนอกผู้เกิดในเมืองกรุง ในฐานะผู้สังเกตการณ์เข้าไปยังเรื่องราวของผู้คนในท้องถิ่นอันห่างไกลของคนเมือง และมุมมองของคนในที่เติบโตในพื้นที่และเข้าใจถึงวิถีความเป็นอยู่ของชาวมุสลิม

หลังจาก “แสนแสบ” ผลงานล่าสุดของปรัชญ์ ที่เป็นส่วนหนึ่งในนิทรรศการกลุ่มธาราพันลึก - the FROZEN ได้จัดแสดงที่เอส เอ ซี แกลเลอรี (SAC Gallery) มาระยะหนึ่งแล้ว เราชวนศิลปินกลับมานั่งพูดคุยถึงที่มาที่ไปของผลงาน และหลายสิ่งหลายอย่างที่ประกอบสร้างขึ้นมาเป็นผลงานชิ้นนี้

[1]

มหานครของประเทศไทยมีชุมชนมุสลิมกระจายตัวอยู่ทั่วไป เช่นกันกับครอบครัวของปรัชญ์ที่มีพื้นเพอยู่หลายที่ ฝั่งพ่อผูกโยงกับชุมชนมุสลิมในบางลำภูและคลองมหานาค ส่วนฝั่งแม่มีถิ่นเดิมอยู่ที่แถบกิ่งเพชร ถนนเพชรบุรี รวมถึงเขตหนอกจอก ย่านมุสลิมใหญ่ของเมืองหลวง

ชาวมุสลิมในกรุงเทพฯ อพยพจากหลายที่มา บ้างเป็นครอบครัวที่เพิ่งย้ายมาไม่กี่สิบปี ขณะที่บางบ้านเป็นเจ้าของที่ดินที่อยู่ต่อกันหลายชั่วคนจนสืบรากไม่ได้

“งานชิ้นนี้เกิดจากการขุดคุ้ยประวัติศาสตร์ เชื่อมโยงไปมาระหว่างกรุงเทพฯ กับคลองแสนแสบว่า ขุดได้ยังไง ทำไมมุสลิมถึงมีที่ดินทำกินมากมายในกรุงเทพฯ”

การเริ่มสืบค้นรากเหง้าของครอบครัวที่เป็นหน่วยเล็กๆ กลับปรับมุมมองไปสู่ภาพใหญ่ขึ้น คือความเชื่อมโยงระหว่าง 2 พื้นที่อันห่างไกล ผ่านการอพยพของชาวมุสลิมจากถิ่นหนึ่งมาสู่ถิ่นหนึ่งในหลายช่วงเวลา โดยเฉพาะจากพื้นที่สามจังหวัดชายแดนภาคใต้ ที่ซึ่งในอดีตมีศูนย์กลางคือรัฐอิสลามอันรุ่งเรืองในชื่อ รัฐปาตานี (Patani State)

ทำเลที่ตั้งของรัฐปาตานีมีลักษณะเป็นอ่าวขนาดใหญ่ เวิ้งน้ำที่โอบรับเป็นกำแพงกั้นคลื่นลมทะเล ทำให้เรือสินค้าต่างมาจอดหลบมรสุม ตรงนี้จึงเกิดเป็นท่าเรือสำคัญของภาคใต้ และเป็นปลายทางเชื่อมคาบสมุทรระหว่างทะเลอันดามันกับอ่าวไทย รวมถึงเป็นบ้านเมืองที่ศาสนาอิสลามตั้งมั่นอย่างเข้มแข็ง

ในช่วงต้นกรุงรัตนโกสินทร์ สยามเข้ายึดครองรัฐปาตานีโดยเบ็ดเสร็จ พร้อมพาผู้ปกครองและกำลังคนเข้ามาในกรุงเทพฯ ชุมชนชาวมลายูจึงเข้ามาอยู่กับชุมชนมุสลิมที่อยู่มาก่อน กระทั่งต่อมาในสมัยรัชกาลที่ 3 พวกเขาจึงถูกเกณฑ์ให้ทำหน้าที่ขุดคลองแสนแสบ ก่อนจับจองพื้นที่อาศัยและทำเกษตรกรรมริมคลองสายใหม่

“การที่ครอบครัวเราเป็นมุสลิมในกรุงเทพฯ เราอาจมาจากภาคใต้ตามประวัติศาสตร์ในอดีต อาจเป็นเชลยสงครามในสมัย ร.1 ที่ถูกจับมาก็ได้ คำถามคือแล้วสุดท้ายเราเป็นคนสามจังหวัดฯ เป็นคนมลายูเหมือนกันรึเปล่า คิดว่าอะไรทำให้ตรงนั้นมันเปลี่ยนไป” ปรัชญ์ตั้งข้อสังเกตถึงวันนี้ ที่บางครั้งเขารู้สึกว่า ชาวมุสลิมในกรุงเทพฯ กลายเป็นคนอื่นในสายตาของคนมมุสลิมภาคใต้ ก่อนเล่าต่อว่า “พองานนี้เราพูดถึงการผลักไปมาของผู้คน ก็เลยรู้สึกว่าการทำงานแสนแสบท้าทายตัวเองมาก”

[2]

ปรัชญ์เกิดที่กรุงเทพฯ แต่ย้ายไปอยู่ภาคใต้ตั้งแต่ 3 ขวบ โตและอาศัยในสามจังหวัดชายแดนภาคใต้มาแล้วกว่าค่อนชีวิต สถานะนี้จึงทำให้เขาสามารถมองเข้าไปยังพื้นที่ด้วยสายตาคนนอก ขณะเดียวกันก็เข้าใจพื้นที่ในมุมคนในไปพร้อมกัน

เขาอธิบายว่า พื้นที่สามจังหวัดชายแดนภาคใต้เป็นบริเวณที่มีอัตลักษณ์สูง ผู้คนส่วนใหญ่นับถือศาสนาอิสลาม พูดภาษามลายู และมีวิถีชีวิตตามหลักศาสนาที่ต่างไปจากกลุ่มคนไทยภาคอื่น

ภาษาเป็นสื่อกลางสำคัญในการสื่อสาร และเป็นหนึ่งในสิ่งที่บ่งบอก “ความเป็นเรา” ของคนที่อยู่ร่วมกัน ในสามจังหวัดชายแดนภาคใต้ นอกจากศาสนาแล้ว ภาษามลายูก็เป็นหนึ่งในสิ่งที่โอบรับความเป็นเราของคนพื้นที่ เช่นเดียวกับกลุ่มคนที่พูดภาษาไทย เมื่อพบเจอคนที่พูดจาต่างภาษาหรือพูดไม่ชัด บางครั้งก็ผลักให้คนนั้นออกไปเป็นคนอื่นโดยไม่ทันรู้ตัว

“ผมเป็นลูกครึ่งต่างจังหวัดกับกรุงเทพฯ พูดมลายูก็ไม่ชัด แต่ก่อนมากรุงเทพฯ ไปหาญาติ ก็จะถูกบอกว่าพูดไทยไม่ชัด เป็นคนบ้านนอก พอเรากลับมาบ้านนอก เราก็พูดภาษาถิ่นไม่ชัด ก็ตั้งคำถามกับตัวเองว่า ทำไมคนถึงผลักกันไปมา มันคือการกอดรัดตัวตนของตัวเองเกินไปหรือเปล่า

“ภาษาอาจเป็นตัวหนึ่งที่ชี้ถึงความเป็นเพื่อนสนิท สนิทสนม คุยกันกลมกลืน ความเป็นเนื้อเดียวกันกับคนท้องถิ่น ภาษาคือสิ่งสำคัญที่สุดที่จะตัดสินว่าเป็นพวกเดียวกับเราไหม เราก็พยายามหาอย่างอื่นว่า ถ้าไม่ใช่ภาษาล่ะ เราเป็นเลือดเนื้อปัตตานีเหมือนกันไหม ฉันสู้คุณได้ไหม ในเมื่อพูดมลายูไม่ได้ สุดท้ายสู้ได้ แต่ก็น้ำหนักไม่พอ”

ไอเดียของนิทรรศการครั้งนี้ ศิลปินจึงอยากชวนมองถึงการที่ใครสักคนต่างกอดรัดความเป็นตัวของตัวเองในท้องถิ่น แล้วปิดกั้นการเปิดรับคนอื่นที่เข้ามา เพียงเพราะเขาคนนั้นมีความแตกต่างจากพวกเรา ไม่ว่าจะในเรื่องศาสนา เชื้อชาติ หรือภาษา

“เราไม่ได้มองกรุงเทพฯ หรือปัตตานีอย่างเดียว แต่เรามองภาพอดีตว่า ต้นตอของการกอดรัดความเป็นตัวเองไว้ทำให้เกิดความเป็นรัฐพันลึก ความเป็นรัฐที่บิดเบี้ยว การที่รัฐมีเกมการเมืองหรือประชาชนไม่มีส่วนร่วม ทำให้เกิดการที่รู้กันแค่ข้างบน”

คล้ายกันกับกรณีของการอพยพของผู้คนจากสงคราม ที่หลายครั้งก็เกิดขึ้นจากข้อตกลงของผู้นำ โดยที่คนตัวเล็กตัวน้อยต้องจำยอมปฏิบัติตาม เคลื่อนย้ายไปมาเหมือนน้ำ และจำต้องปรับตัวตามที่อยู่ใหม่ แล้วอัตลักษณ์บางอย่างที่มีก็ถูกกลืนหายไป

[3]

ย้อนไปเมื่อปี 2564 - 2565 ในนิทรรศการศิลปะโอรังซิแย/ออแฆนายู ปรัชญ์เคยแสดงผลงานที่ตั้งคำถามถึง “ตัวตน” และ “เชื้อชาติ” ของชาวไทยกับมลายูมาแล้วครั้งหนึ่ง ตอนนั้นเขาตั้งใจเล่าถึงความเป็นอื่นของคนในพื้นที่ที่ผลักคนบางกลุ่มออกมา ผ่านมา 2 ปี เขาหยิบเรื่องราวตรงนั้นมาต่อยอด ปรับมุมมอง แล้วพูดถึงอีกครั้งเพื่อสะท้อนนัยถึงความหลากหลายในสังคมไทยที่เกิดขึ้น ผ่านการยักย้ายถ่ายเทของกลุ่มคน

“แสนแสบ” ไม่เพียงแต่เล่นล้อกับชื่อพื้นที่ ทว่ายังหมายรวมถึงชาวมุสลิมที่อยู่ในนั้น

ภาพแรกหลังจากเข้ามาในห้องจัดแสดงชั้น 2 ของเอส เอ ซี แกลเลอรี ประกอบไปด้วยตู้กับข้าว 2 ตู้ ด้านในบรรจุสิ่งของต่างๆ แท่งปูนที่วางดอกไม้สีทองอร่ามอยู่ด้านใน พร้อมกับแสงไฟเค้าโครงเหมือนโฉนดที่ดินที่ถูกยิงเข้าหากำแพง และผลงานศิลปะจัดวางพิงอยู่ที่กำแพง

“เราคิดอย่าง Conceptual เลย ทุกอย่างมีความหมาย มี Concept ไม่มีอันไหนที่ไม่มีเรื่องราว”

โฉนดที่สื่อถึงความเป็นเจ้าของที่ดินของครอบครัว, ดอกไม้สีทองที่สะท้อนถึงเครื่องบรรณาการ หรือปูนซีเมนต์ที่ถูกนำมาพูดถึงการก่อร่างสร้างเมือง คือบางส่วนจากหลายสิ่งของที่ศิลปินนำมาใช้เพื่อถ่ายทอดเรื่องราวต่างๆ ในผลงานครั้งนี้

“หนึ่ง ผมเชื่อเรื่อง Material, Object, วัตถุสำเร็จรูป, วัตถุเก็บตก สอง คือเนื้อหาที่นำมาใช้ผ่านการรีเสิร์ช สาม ตัวชี้นำคือประสบการณ์ที่มีต่อเรื่องที่ผมใช้ ถ้าคนที่มีประสบการณ์ร่วมกัน มีแบ็กกราวน์เป็นส่วนหนึ่งของประวัติศาสตร์มลายูปัตตานีหรือความเป็นรัฐ เขาก็จะเข้าใจแล้วก็อินเร็ว

“คนที่ไม่รู้อาจไม่เข้าใจ อาจนึกไม่ออก แต่พอเราบอก Background ทั้งหมดว่า มันคือการ Blend in, การเสียดินแดน, การก่อร่างสร้างเมือง หรือประวัติศาสตร์ปาตานี ประวัติศาสตร์สยามกว้างๆ หรือถ้าเป็นนักประวัติศาสตร์โบราณคดี ก็จะเข้าใจเลย”

[4]

ขณะที่ประวัติศาสตร์กระแสหลักมักพูดถึงความเป็นไทยอันหมายถึงทั้งพื้นที่ขวานทอง โดยหลงลืมไปว่าในแต่ละท้องถิ่นต่างมีตัวตนเป็นเอกลักษณ์เฉพาะ ชั่วขณะหนึ่งหลังจากฟังเรื่องราวจากศิลปิน นิทรรศการครั้งนี้ก็พาเราหันมามองความหลากหลายของผู้คน ที่ปะติดปะต่อกันคล้ายจิ๊กซอว์ จนกลายเป็นประเทศชาติขึ้นมา

แม้ธีมงานดูละเอียดอ่อนในมุมมองทางสังคมและการเมือง แต่ศิลปินก็เผยว่า เนื้อหาที่ซุกซ่อนอยู่ในผลงานของเขาเป็นเรื่องจริงที่ผ่านการหาข้อมูลทั้งหมด และขณะเดียวกันก็เปิดโอกาสให้ผู้ชมได้ตีความตามแต่ประสบการณ์และการรับรู้ของแต่ละคน

“ตัวงานพูดถึงสิ่งที่เกิดขึ้นจริง เป็น Object ที่เป็นผลของอดีต เราอยากให้คนเห็นภาพกว้างมากกว่าความเป็นรัฐที่มาจัดสรรและตกลงกันเบื้องบน แต่เรื่องที่ผมเล่าคือเรื่องของประชาชน และตั้งคำถามกับสิ่งที่ถูกจัดการและสิ่งที่ถูกทำให้เป็นมากกว่า เลยไม่ได้คิดซับซ้อนในการเล่าเรื่องว่าเป็นประเด็นละเอียดอ่อน”

“งานแสนแสบทำให้เห็นภาพกว้างของการกอดอีกสิ่งหนึ่งจนไม่ปล่อย เราก็แค่หยิบวัตถุเหล่านั้นมาให้เห็นผลกระทบที่ตามมา การเคลื่อนย้าย ปัญหาต่างๆ ที่ซ่อนอยู่ มีรูโหว่ มีการเปลี่ยนแปลง แล้วสะท้อนกลับมาที่ตัวเองว่า ทุกอย่างมีมิติที่ซ่อนอยู่” ศิลปินขมวดสรุปก่อนจบการสนทนา

นิทรรศการนี้เปิดโอกาสให้ทุกคนได้ตีความสิ่งที่อยู่ตรงหน้า โดยขึ้นอยู่กับว่า มองผ่านแว่นตาอะไร หากคุณมองด้วยแว่นตาของประวัติศาสตร์ โบราณคดี หรือรัฐไทย ผลลัพธ์ก็ออกมาอีกแบบหนึ่ง หากมองด้วยแว่นตาแบบชาวท้องถิ่นมลายู ภาพในหัวก็จะเป็นอีกลักษณะหนึ่ง และเมื่อไรก็ตามที่มองด้วยใจเป็นกลาง ผลงานชิ้นนี้ก็พร้อมพาออกไปเห็นมุมมองใหม่ๆ เช่นกัน

The phrase “Three Southern Borders” is often presented alongside the word “violence”, which seems to follow it like a shadow. However, if we look deeper and try to understand, we find that this region, situated at the end of the axe handle, is a centre of diverse cultures and has a unique identity.

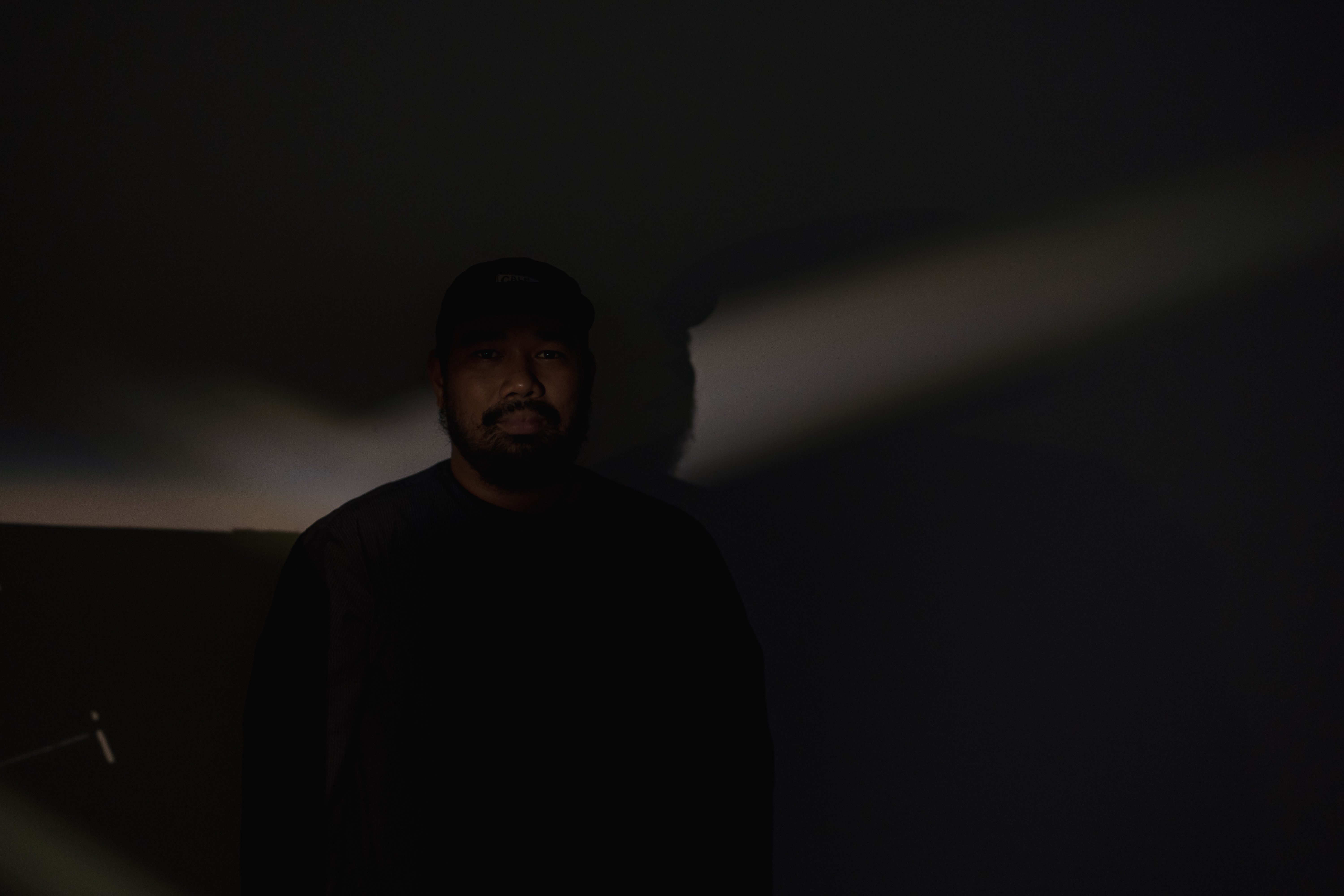

Prach Pimarnman is an artist from the southern border region who creates works related to the land of his ancestors. His past works have deeply conveyed Malayness in many aspects, interestingly combining the perspectives of both an “insider” and an “outsider”.

He offers the perspective of an outsider, born in the capital city, observing the stories of people in remote areas. Simultaneously, he provides the perspective of an insider, having grown up in the area and understanding the way of life of Muslims.

After “Saen Saep”, Pimarnman’s latest work, which is part of “The FROZEN” group exhibition, was exhibited at SAC Gallery for some time. We invited the artist to talk about the origins of the artwork and the many elements that make up this piece.

[1]

The metropolis of Thailand is dotted with Muslim communities, much like Pimarnman’s family, which has many roots in Bangkok. His father’s side is connected to the Muslim communities in Bang Lamphu and Khlong Maha Nak, while his mother’s side originally came from the King Phet area, Petchburi Road, and Nong Chok district, a major Muslim area of the capital.

Muslims in Bangkok have migrated from many places. Some families have only moved here in recent decades, while others have owned land for generations, making it difficult to trace their roots. “This work is the result of digging up history, connecting Bangkok and Khlong Saen Saep: how did they dig it? Why do Muslims have so much land in Bangkok?”

Investigating the roots of a small family unit shifts to a bigger picture: the connection between the two distant areas through the migration of Muslims at various times, especially from the three southern border provinces. In the past, these provinces were part of a prosperous Islamic state called Patani State.

Patani State is located in a large bay with a natural barrier that blocks waves and wind, allowing cargo ships to dock and take shelter from monsoons. This made it an important port in the South, serving as a destination connecting the Andaman Sea and the Gulf of Thailand, as well as being a major Islamic state.

In the early Rattanakosin period, Siam completely occupied Patani State, bringing its king, noblemen, and people to Bangkok. The Malay community therefore integrated with the existing Muslim community in Bangkok. Later, during the reign of King Rama III, they were conscripted to dig the Saen Saep Canal before settling along the new canal to live and farm.

“My family is Muslim in Bangkok. We may have come from the South according to past history. We may have been prisoners of war during the reign of King Rama III who were captured. The question is, in the end, are we from the three provinces or Malays as well? What do you think has changed that?”

Pimarnman observed about the present day, when he sometimes felt that Muslims in Bangkok have become strangers in the eyes of Muslims in Southern Thailand. He continued, “When I speak about this work, I speak about the displacement of people, so I feel that working on Saen Saep is very challenging.”

[2]

Pimarnman was born in Bangkok but moved to the south of Thailand when he was 3 years old. He has lived and grown up in the three southern border provinces for more than half of his life. This dual status allows him to see the area through the eyes of an outsider while also understanding it from an insider’s perspective.

He explains that the three southern border provinces have a strong sense of identity. Most people are Muslims, speak Malay, and have a religious way of life that differs from other groups of Thai people.

Language is an important medium of communication and is one of the key indicators of the identity of people living together in the three southern border provinces. In addition to religion, Malay is one of the things that defines the local people’s identity. Similarly, when people speak Thai and encounter others who speak different languages or do not speak clearly, they sometimes push them away as outsiders without realising it.

“I am half provincial and half Bangkokian. I do not speak Malay clearly. Before coming to Bangkok to visit relatives, people would say that I do not speak Thai clearly, that I am from the countryside. When I returned to the countryside, I could not speak the local dialect clearly. So I asked myself why people pushed each other away. Is it because they hold on to their own identity too much?

“Language may be one thing that indicates closeness, intimacy, and harmony with the local people. It is the most important factor in determining whether we belong to the same group. We tried to find something else; if not language, are we the same race of Pattani? Can I connect with you? Since I can’t speak Malay, in the end, I tried, but it’s not enough.”

With this exhibition, the artist wants to invite people to reflect on how embracing one’s own local identity can block the acceptance of others who come in just because they are different in terms of religion, race, or language.

“We don’t only look at Bangkok or Pattani; we look at the past and see how the origins of embracing one’s own identity lead to a deep, sometimes distorted state. When the state plays politics or the people don’t participate, it leads to a situation where only those at the top are informed.”

This is similar to the case of people migrating due to war, which often happens due to the agreements of leaders, leaving ordinary people to comply, move around like water, and adapt to their new place of residence. Consequently, some aspects of their identities are lost.

[3]

Back in 2021-2022, at his old art exhibition, Pimarnman exhibited a work that questioned the “identity” and “race” of Thais and Malays. At that time, he intended to tell the story of the otherness of the people in the area that pushed some groups out. After 2 years, he picked up that story to expand on and talk about it again to reflect the diversity in Thai society that has resulted from the movement of various groups.

“Saen Saep” is not only the name of the canal but also refers to the Muslims living there. The first image upon entering the exhibition room on the 2nd floor of SAC Gallery consists of two food cabinets. Inside them are various items: cement bars with golden flowers, lights resembling land title deeds projected onto the wall, and artworks leaning against the wall.

“I think conceptually. Everything has meaning, has a concept, nothing is without a story.”

The title deed represents his family’s ownership of the land, the golden flowers reflect tribute, and the cement signifies the construction of the city. These are some of the many objects the artist uses to convey various stories in this artwork.

“One, I believe in material objects. Two, the content used is based on research. Three, the guide is the experience with the subject matter that I use. If people who have shared experiences have a background that is part of the history of Malay or the Patani state, they will understand and absorb it quickly.

“People who don’t know may not understand, may not be able to imagine it. But when we explain the entire background—that it involves blending in, the loss of territory, the establishment of a city, or the history of Patani state and Siam, or if they are archaeologists—they will understand immediately.”

[4]

Mainstream history often talks about Thainess as encompassing the entire Golden Axe area, forgetting that each region has its own unique identity. After listening to the artist’s story, this exhibition allows us to look at the diversity of people who fit together like a jigsaw puzzle to form a nation.

Although the theme of the work may seem sensitive in terms of social and political perspectives, the artist reveals that the content hidden in his work is based on true stories that have been researched. At the same time, it opens up opportunities for viewers to interpret it according to their own experiences and perceptions.

“The work itself talks about what happened. It is an object that is a result of the past. I want people to see a broader picture than what the state allocates and agrees upon with the higher-ups. The story I tell is about the people and questions what has been managed and made to be more than that. So I don’t think too complicatedly about telling the story as a sensitive issue.

“Saen Saep gives us a broad picture of holding onto something and not letting go. I just pick up those objects to see the consequences, the displacement, the problems that are hidden, the holes, the changes, and then reflect back to ourselves that everything has a hidden dimension”, the artist concluded before ending the conversation.

This exhibition opens up opportunities for everyone to interpret what is in front of them, depending on the personal lens they look through. If you look at it through the lens of history, archaeology, or the Thai state, the result will be different. If you look at it through the lens of a local Malay, the image in your head will be different. And whenever you look at it with an open mind, this work is ready to take you out to see new perspectives as well.

Tuesday - Saturday 11AM - 6PM

Close on Sunday, Monday and Pubilc Holidays

For more information: info@sac.gallery

092-455-6294 (Natruja)

092-669-2949 (Danish)

160/3 Sukhumvit 39, Klongton Nuea, Watthana, Bangkok 10110 THAILAND

This website uses cookies

This site uses cookies to help make it more useful to you. Please contact us to find out more about our Cookie Policy.

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied in accordance with our privacy policy (available on request). You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.