OPEN HOURS:

Tuesday - Saturday 11AM - 6PM

Close on Sunday, Monday and Pubilc Holidays

For more information: info@sac.gallery

(English is below)

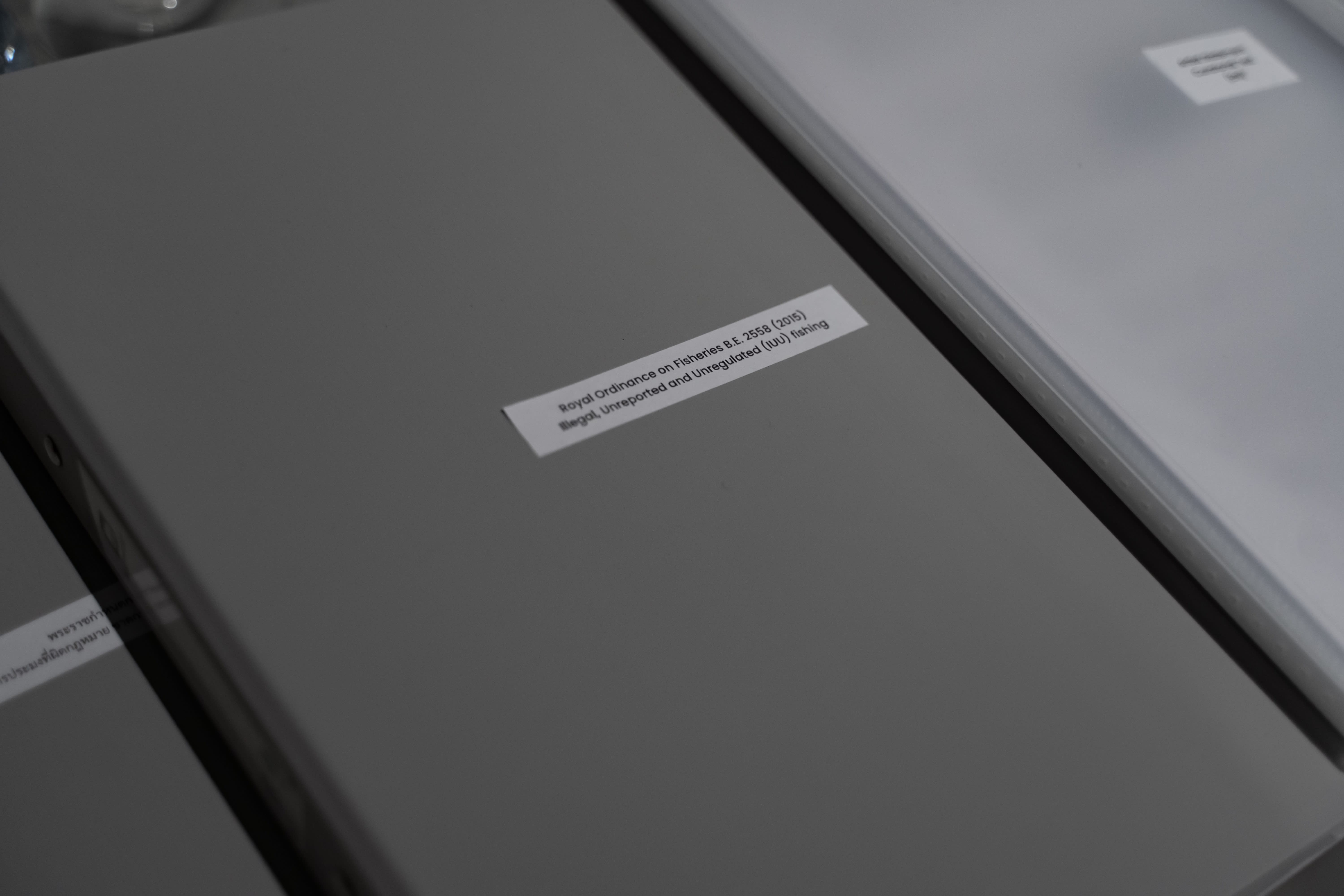

ปี 2015 ประเทศไทยได้รับการแจ้งเตือนจากสหภาพยุโรป (European Union: UN) ว่า เป็นประเทศที่เสี่ยงต่อการทำประมงผิดกฎหมาย ขาดการรายงาน และไร้การควบคุม (Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing : IUU) โดยให้ติด ‘ใบเหลือง’ หรือไม่ให้ความร่วมมือไว้ก่อน จนกว่าจะมีการแก้ไข และหากยังปล่อยไว้โดยไม่มีการดำเนินการใดๆ จะนำไปสู่ขั้นเลวร้ายกว่านั้นคือออกใบแดงหรือคว่ำบาตรผลิตภัณฑ์ประมงของประเทศไทย

รัฐบาลในขณะนั้นซึ่งมาจากการรัฐประหารพยายามทุกวิถีทาง อาศัยกลไกอำนาจทุกวิธีเพื่อให้สหภาพยุโรปปลดใบเหลือง ส่วนหนึ่งคือการออกกฎหมายที่ขัดกับหลักกฎหมายทั่วไป โดยมีมาตรา 44 เป็นทางลัดช่วยอำนวยความสะดวก ให้กฎหมายต่างๆ ผ่านออกมาอย่างง่ายดาย ทั้งห้ามการทำประมงโดยใช้อวน จัดระเบียบเรือใหญ่น้อย หรือแม้กระทั่งการกำหนดให้เรือทุกลำมีเอกสารอนุญาตในการออกเรือ ซึ่งเหล่านี้ไม่เพียงแต่ส่งผลต่อกิจการประมงรายใหญ่ แต่ยังกระทบต่อชาวประมงพื้นบ้าน และลามไปถึงวิถีชีวิต ความเป็นอยู่ รวมถึงวัฒนธรรม

ปี 2019 หลังจากผ่านไปเกือบ 4 ปี ความมุมานะของรัฐบาลก็สำเร็จ สหภาพยุโรปปลดใบเหลืองการประมงของประเทศไทย ท่ามกลางเสียงโห่ร้องดีใจ ยกย่องเป็นหนึ่งในผลงานชิ้นโบแดงของรัฐบาลทหาร กลบกลืนเสียงระทมทุกข์ของชาวประมงพื้นบ้านในจังหวัดชายทะเลกว่า 22 จังหวัด ที่ระหว่างทางนั้นสิ้นเนื้อประดาตัว ต้องเปลี่ยนอาชีพที่สืบทอดกันมาแต่บรรพบุรุษ เรือที่เคยเป็นอุปกรณ์ทำมาหากินถูกจอดทิ้งไว้ และกว่าใบเตือนจะหลุดหายไป เรือเหล่านั้นก็ไม่ได้ลอยอยู่บนท้องน้ำดังเดิมเสียแล้ว

01

ปี 2021 พิชัย พงศาเสาวภาคย์ ศิลปินร่วมสมัยชาวสงขลา มีโอกาสลงไปเยี่ยมพี่สาวที่จังหวัดปัตตานี เขาพบว่า กิจการเครื่องมือประมงของพี่สาวดูซบเซาลง เครื่องไม้เครื่องมือในการหาปลาอย่างอวนยังคงเหลือค้างอยู่ในร้าน เพราะถูกจัดเป็นอุปกรณ์ผิดกฎหมาย ตามพระราชกำหนดการประมง พ.ศ. 2558 สิ่งนี้นำทางให้เขาออกเดินทางตามหาเรื่องราวของอาชีพประมงในจังหวัดปัตตานีที่ได้รับผลกระทบจากข้อบังคับของกฎหมาย และยิ่งหาก็พบว่า ปลายทางของเรือประมงที่ถูกปลดระวางคือซากไม้ในพื้นที่ทุบทำลาย

“ความน่าสนใจอยู่ตรงที่ circle ของเรือมันดูแปลกๆ จากเรือลำหนึ่งกลายไปเป็นเศษไม้ เลยตั้งใจว่าวันหนึ่งเราจะต้องลงไปไซต์ที่มีการทุบทำลายเรือ พอไปถึงไซต์นั้นอยู่ที่ตำบลบานา จังหวัดปัตตานี เศษซากเรือเยอะมาก เราก็คิดว่าเขาไม่มีที่เก็บหรืออย่างไร ทำไมถึงใช้วิธีนี้ และหลังจากทุบทำลายไปแล้วมันไปไหน ก็อยากรู้ที่มาที่ไปของเส้นทางของมันว่า วัสดุพวกนี้มันไปไหน นี่คือจุดเริ่มต้นที่เรารู้สึกกับมันมากๆ”

พิชัยลงพื้นที่หาข้อมูลในชุมชนริมทะเลต่างๆ ในจังหวัดปัตตานี โดยมีคนท้องถิ่นช่วยนำทางไป ส่วนหนึ่งเพื่อความไว้เนื้อเชื่อใจ รวมถึงช่วยสื่อสารกับชาวบ้านในท้องถิ่นที่ใช้ภาษายาวี

เขาตระเวนพูดคุยกับชาวบ้านที่ข้องเกี่ยวกับอุตสาหกรรมประมง ทว่าเรือประมงลำหนึ่งสามารถขยายไปยังผู้มีส่วนร่วมได้มากกว่าเพียงแค่คนจับปลา พิชัยสัมภาษณ์ทั้งคนทำอาชีพต่อเรือ คนทาสีเรือ ไปจนถึงคนวาดลวดลายของเรือกอและ เพื่อหาว่าพวกเขาได้รับผลกระทบอย่างไรบ้าง

“ไม่มีงานเลยตอนนี้ งานมันหาย งานปกติไม่เคยว่าง ตอนนี้ไม่มีงานต่อเรือเลย” คือบางเสียงที่พิชัยได้ฟัง ซึ่งเขารู้สึกว่า เนื้อหาที่สื่อผ่านคำพูดนี้ นอกจากเรื่องอาชีพแล้วคือความลึกของปัญหาที่ซ่อนไว้ เช่นช่างวาดลายเรือกอและที่สืบทอดจิตวิญญาณงานช่างตั้งแต่บรรพบุรุษ แต่กลับต้องมาทิ้งสมบัติของครอบครัวไป

การลงพื้นที่ครั้งแรกทำให้เขาได้ข้อมูลมาประมาณหนึ่ง และช่วยนำทางในการหาข้อมูลครั้งที่ 2 ได้ตรงเป้ามากขึ้น พิชัยเริ่มมองหาว่า แล้วชาวประมงกลุ่มไหนได้รับผลกระทบจริงๆ และเป็นสิ่งที่ตัวเขาอยากนำเสนอจริงๆ คำตอบคือ ‘กลุ่มชาวประมงพาณิชย์’ ซึ่งยังสามารถเชื่อมโยงไปถึงการซื้อขายเรือ อันนำไปสู่การทุบทำลายในที่สุด

พิชัยรับฟังสิ่งที่เกิดขึ้นกับชาวบ้านกว่า 10 ครอบครัว บ้างเป็นสามีภรรยา บ้างเป็นแม่ลูก เรือในการประกอบอาชีพของพวกเขาเหล่านี้ เมื่อจอดทิ้งร้างไร้หน้าที่จึงถูกนำไปขายเป็นซากไม้ พิชัยเดินทางไปยังตำบลบานา ก่อนจะพบกับสุสานเรือขนาดมหึมา ที่ซึ่งเรือลำงามที่เคยล่องในน้ำ กลายเป็นไม้ขนาดต่างๆ ริมชายหาด บางส่วนถูกส่งต่อไปทำเป็นฟืนเพื่อต้มปลากะตัก หนึ่งในวัตถุดิบทำน้ำบูดู ผลิตภัณฑ์พื้นบ้านขึ้นชื่อของจังหวัด

“ตอนลงพื้นที่พบว่า process ของซากไม้ทั้งหมดถูกกระจายไปยังหมู่บ้านต่างๆ หมู่บ้านนั้นก็อยู่ในตำบลบานา ที่เป็นตำบลที่มีการทุบเศษซากเรือด้วย มันมีความ amazing ตรงที่ทุกอย่างเกิดขึ้นในพื้นที่เดียวกันหมด เป็นที่ที่รัฐทิ้งเรือจนเป็นซากไม้ แล้วก็ส่งต่อให้ชาวบ้าน เอาไปทำฟืนต้มปลากะตัก แล้วก็ถูกผลิตเป็นน้ำบูดู อาหารพื้นบ้านของคนที่นั่น”

การได้คุยกับกลุ่มชาวประมงหลายคน ยิ่งทำให้พิชัยรู้สึกอินกับความรู้สึกของการสูญเสียที่ชาวบ้านได้รับ เขารู้สึกว่า เรือไม่เพียงแต่เป็นวัตถุหนึ่งที่มีแล้วจะขายออกไปเมื่อไรก็ได้ หากแต่ยังมีเรื่องของวิถีชีวิตและจิตใจที่ซ่อนอยู่เบื้องหลัง

“เราจะเห็นว่า กว่าคนจะได้เรือหนึ่งลำมาหาปลา หากิน มันยากลำบาก และเขาไม่ได้ทำปีสองปีก็เลิก แต่เขาทำตั้งแต่รุ่นพ่อ บางคนเรียน ป.3 ป.4 ก็ออกมากเป็นไต๋เรือ ลูกเรือ คือเป็นชีวิตบนสายน้ำในพื้นที่นั้นจริงๆ” พิชัยเสริม

ระหว่างนั้นพิชัยได้ นิ่ม นิยมศิลป์ ภัณฑารักษ์อิสระ มาช่วยดูด้านเนื้อหาในโปรเจกต์ ระหว่างเรื่องราวจากฝั่งชาวบ้านกับฝั่งของรัฐบาลผู้บังคับใช้กฎหมาย เนื่องจากเนื้อหามีความซับซ้อนและประกอบด้วยหลากหลายฝ่าย

“ตอนพี่พิชัยทำโปรเจกต์นี้มี 2 มุมที่ develop มุมแรกคือรีเสิร์ช อีกมุมคือการบาลานซ์ เพราะพี่พิชัยสัมภาษณ์ชาวบ้าน แต่กลุ่มที่เราอยากได้ เพื่อมาบาลานซ์เรื่องสตอรี่ คือกลุ่มของภาครัฐ คนที่ออกกฎหมาย” นิ่มอธิบาย

อีกจังหวะดีระหว่างการทำงาน คือทั้งคู่มีโอกาสได้พบกับนักวิชาการประมง จากกรมประมง ที่ช่วยให้ข้อมูลต่างๆ ตั้งแต่ต้นสายยันปลายเหตุของเรื่องราวทั้งหมดที่มาจากฝั่งภาครัฐ ทำให้ความน่าสนใจของโปรเจกต์นี้มีเสียงจากสองฝั่งอย่างสมดุล

“จำได้ว่าตอนแรกประเด็นค่อนข้างเยอะมาก นอกจากเรื่องซื้อเรือ ยังมีหลายเรื่องข้อกฎหมายที่ออกมาเยอะ แล้วส่งผลกระทบหลายฝ่าย แต่แล้วเราก็รู้สึกว่า การทำงานนี้มันเป็นโปรเจกต์ที่จะใหญ่มาก เพราะอุตสาหากรรมประมงมันคอมเพลกซ์ เลยคุยกันว่า อันนี้เป็นนิทรรศการแรกที่พี่พิชัยทำประเด็นเรื่องนี้ คิดว่าไม่สามารถสรุปทุกอย่างได้หมดในนิทรรศการเดียว คือต้องเป็น on going”

ภัณฑารักษ์ของนิทรรศการนี้เล่าถึงการทำงานร่วมกับศิลปิน ซึ่งยังเป็นครั้งแรกที่ทั้งคู่ได้ร่วมงานกัน

หลังจากลงพื้นที่รวบรวมข้อมูลและกระบวนการออกแบบ-จัดทำชิ้นงานกว่า 3 ปี จึงออกมาเป็น “Net Loss” นิทรรศการเดี่ยวครั้งใหม่ของพิชัย โดยมีนิ่มเป็นภัณฑารักษ์ จัดแสดงที่เอส เอ ซี แกลเลอรี (SAC Gallery) โดยครั้งนี้เขาตั้งใจบอกเล่าผลกระทบและความสูญเสียต่างๆ ที่ชาวประมงพื้นบ้านได้รับ ผ่านผลงานศิลปะทั้งภาพถ่าย จิตรกรรม และศิลปะจัดวาง

02

จากริมทะเลในจังหวัดปัตตานีสู่หอศิลป์กลางเมือง เศษซากไม้ของเรือประมงกลายเป็นผลงานศิลปะชื่อ “แม่ย่านาง” ศิลปะจัดวางชิ้นใหญ่และชิ้นแรกที่ได้พบทันทีที่เข้าสู่ห้องจัดแสดง

“แน่นอนว่า งานออกมาจากข้อมูลที่เราได้มา มันถูกแปลงภาพมาจากตรงนั้น เราพยายามให้มันใกล้ที่สุดที่จะเข้าถึง source ที่เราได้มา” ศิลปินเล่าที่มาของผลงานแม่ย่านาง “เราอยากให้ผู้ชมเห็นภาพจริงว่า มีวัสดุจริง ที่อยู่ในสถานที่จริง และเราเคลื่อนย้ายมาในพื้นที่ของอาร์ตสเปซได้ ซึ่งจริงๆ มันยากมาก ที่เราจะเอาชิ้นส่วนออกนอกพื้นที่ที่มีการควบคุมค่อนข้างเข้มงวด”

ขณะที่ผนังด้านหลังของผลงานแม่ย่านาง มีภาพถ่ายชื่อ “คุณค่าระหว่างมนุษย์และธรรมชาติ” แม้จะเป็นผลงานเก่าเมื่อ 2 ปีที่แล้ว แต่ศิลปินมองว่า การที่ผลงานทั้งสองชิ้นมาอยู่ด้วยกัน จะช่วยขับเน้นความหมายของงานศิลปะได้ชัดเจนมากขึ้น รวมถึงยังเชื่อมโยงไปถึงเรื่องของสิ่งแวดล้อมที่เขานำเสนอมาก่อนหน้านี้

“เรือลำหนึ่งก็มาจากต้นไม้ต้นหนึ่ง ถ้าไม่มีต้นไม้ เรือก็ไม่เกิด มนุษย์ก็ใช้ธรรมชาติ ใช้ประโยชน์จากธรรมชาติ พอได้ประโยชน์แล้ว วันหนึ่งมนุษย์ก็ลืมประโยชน์ของธรรมชาติอย่างง่ายดาย ทิ้งก็คือทิ้ง เผาก็คือเผา สุดท้ายธรรมชาติก็เป็นเพียงตัวตอบสนองความต้องการของมนุษย์เท่านั้นเอง” พิชัยเล่า

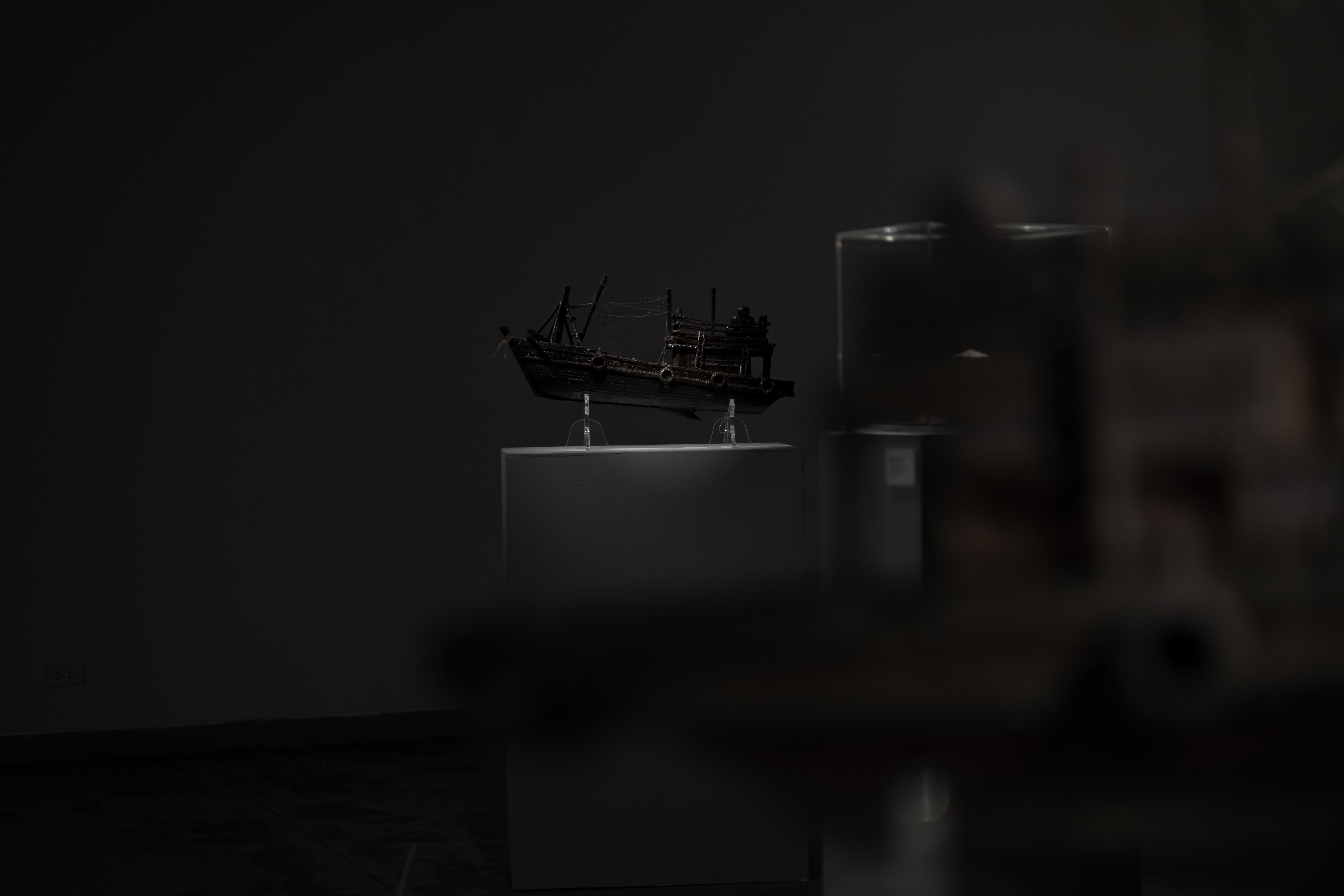

เมื่อเข้าไปสู่ห้องจัดแสดงส่วนที่สอง บางส่วนของซากเรือกลับมาเป็นลำเรือสมบูรณ์อีกครั้งผ่านผลงาน “อนุสรณ์นำโชค 3” และ “ลาภประเสริฐ” คือประติมากรรมเรือประมง 2 ลำในขนาดย่อส่วน ที่เบื้องหลังคือการนำขี้เถ้าหลังจากการเผาเศษไม้เรือ และเศษเหล็กน็อตกับตะปูเรือที่ฝนเป็นผง นำมาย้อนวัฏจักรของเรือประมงด้วยการปั้นคืนรูปทรงดังเดิม พร้อมทั้งนำชื่อของเรือที่ถูกทุบทำลายมาใช้เป็นชื่อผลงาน ซึ่งส่วนหนึ่งของวิธีการทำงานชิ้นนี้ คือการที่ศิลปินได้ทดลองไปกับวัสดุต่างๆ ที่มี เพื่อสร้างสรรค์ออกมาเป็นผลงานศิลปะ

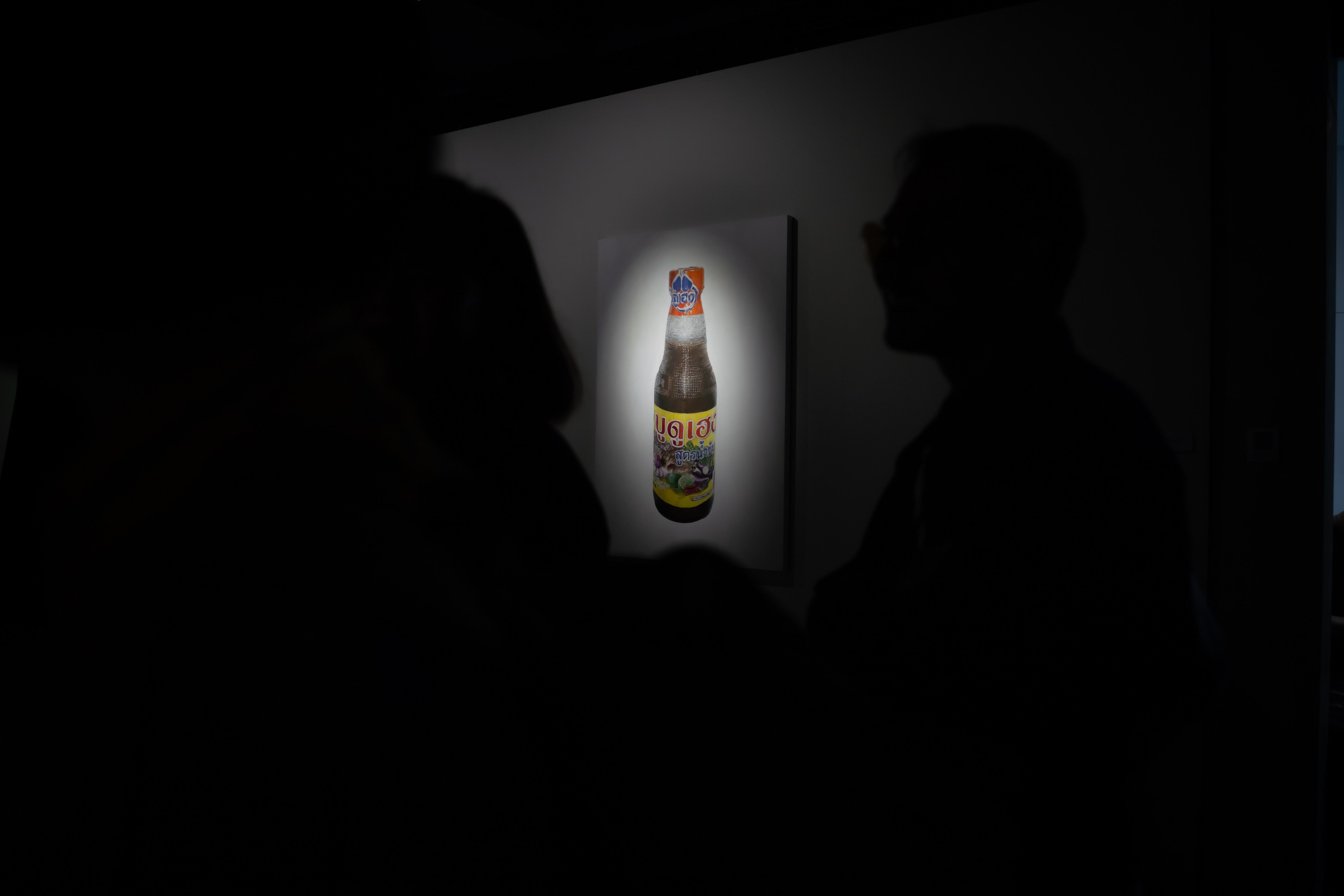

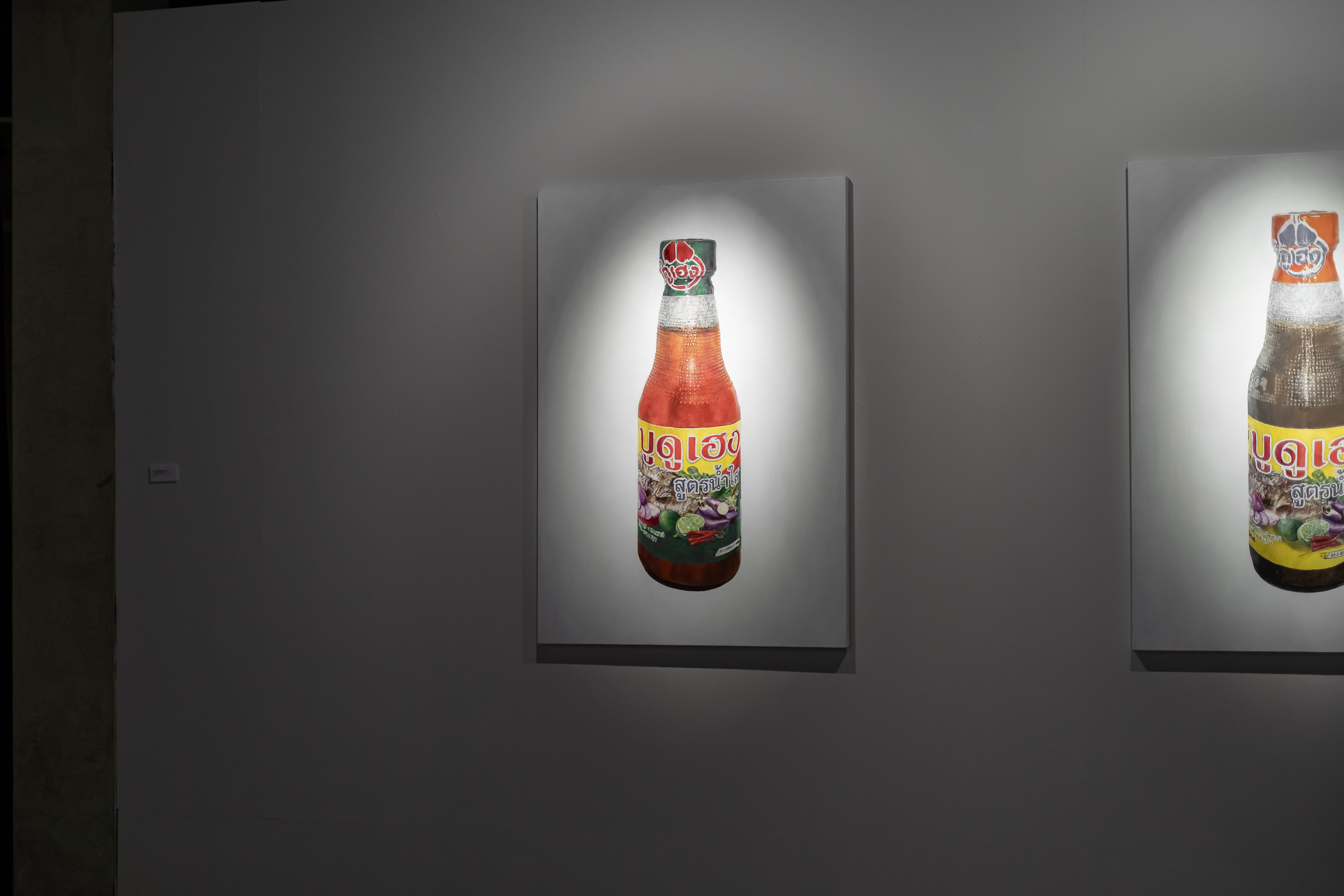

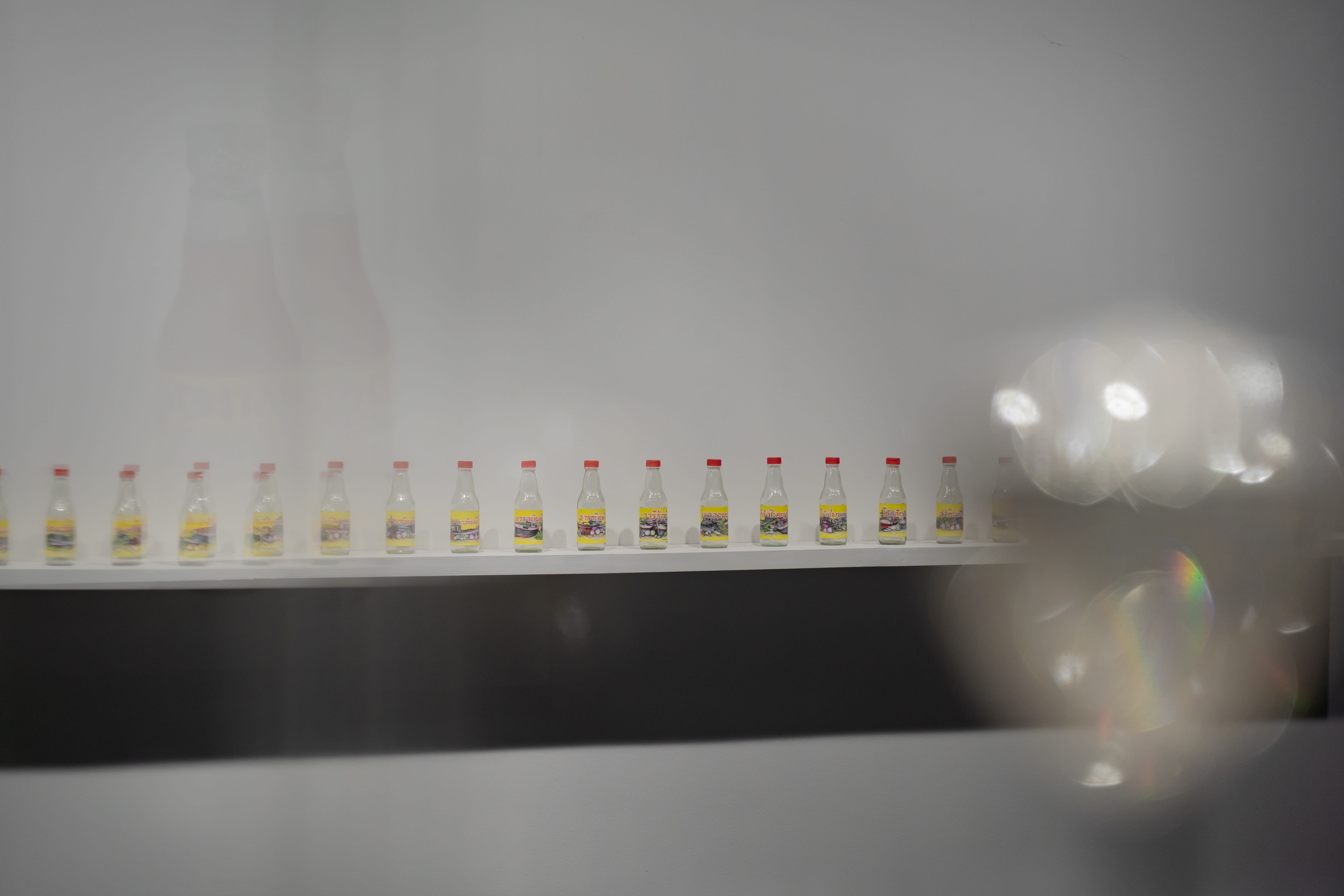

ขณะเดียวกันในนิทรรศการครั้งนี้ พิชัยยังเสนอภาพปลายทางอันหน้าเศร้า และหน้าที่ที่เปลี่ยนไปของเรือลำเล็กลำน้อย 48 ลำ ที่แปลงสภาพจากเรือสู่ซากไม้ และสุดท้ายกลายเป็นฟืนที่นำไปต้มปลาเพื่อทำน้ำบูดู ในผลงาน “48 เรือที่สูญเสีย” ศิลปะจัดวางขวดแก้วน้ำบูดู 48 ขวด ที่ตีฉลากเป็นชื่อของเรือต่างๆ ทั้ง 48 ลำ และภาพเพนติง “บูดูน้ำข้น” กับ “บูดูน้ำใส” เพื่อชวนผู้ชมขบคิดหาคุณค่าของเรือลำหนึ่ง ว่าแท้จริงแล้วเรือเหล่านี้มีประโยชน์ในฐานะอะไรกันแน่

“ชาวบ้านเขารักทะเลมาก เขารักสัตว์น้ำทุกตัวที่เอามาขาย ชาวประมงเองเขารู้ว่าอะไรคือการทำลาย อะไรคือการใช้ประโยชน์กับมันแล้วเกิดคุณค่า เราเชื่อว่าคนทำอาชีพประมง 20-30 ปี ตั้งแต่รุ่นพ่อ เขาจะไม่ทุบหม้อข้าวตัวเองให้หมดไป ไม่ส่งต่อถึงลูกหลาน ก็คงไม่ใช่

“ความจริงใจแบบนี้ทำให้เราเห็นภาพว่า เขาไม่ใช่คนที่ทำลายธรรมชาติ ปลาแต่ละตัวที่จับ เขารู้ว่าเป็นอายุขัยที่ปลาตัวนี้ถึงขั้นตอนของการกินแล้ว แต่แน่นอนว่า มีกลุ่มที่ไม่รู้กฎหมาย ไม่รู้วิธีการรักษาปลาตัวเล็กๆ อย่างคนที่ใช้อวนตาถี่ ที่เขายังไม่สนใจเรื่องนั้น แต่แน่นอนว่า ชาวประมงส่วนใหญ่ที่ได้คุย เขารู้สึกรักสิ่งที่ทำอยู่ เป็นวิถีชีวิตของเขา เป็นครอบครัวของเขา เป็นบ้านของเขา และเขาก็เป็นคนที่รักธรรมชาติ”

นิทรรศการ “Net Loss” ยังมีรายละเอียดซับซ้อน ตื้นลึกหนาบาง และแง่มุมต่างๆ ที่ซุกซ่อนอยู่ในงานแต่ละชิ้น ซึ่งแน่นอนว่าศิลปินไม่อาจนำเรื่องราวได้รับฟังและค้นคว้ามาสื่อสารได้หมดในครั้งเดียว งานครั้งนี้จึงเป็นเหมือนจุดเริ่มต้นเพื่อเชื้อเชิญให้ผู้ชมได้ตระหนักถึงเสียงเล็กๆ ที่ได้รับผลกระทบจากการออกนโยบายบางอย่างเพื่อปกป้องธรรมชาติ โดยที่ผู้มีอำนาจอาจไม่ได้คำนึงถึงการทำลายบางสิ่ง อย่างเช่นวิถีชีวิตบนสายน้ำของลูกน้ำเค็ม

ขณะเดียวกันก็ไม่สามารถเล่าโดยเอนเอียงหรือเพียงฝั่งเดียวได้ เพราะในอีกมุมหนึ่ง รัฐที่ได้รับใบเหลืองมาเป็นตัวกระตุ้น จึงไม่อาจนิ่งนอนใจและมีความจำเป็นที่จะต้องออกกฎหมายช่วยควบคุมบางสิ่งบางอย่างที่ยังไม่ถูกต้อง เพื่อไม่ให้เรื่องราวบานจนปลายส่งผลกระทบกับทั้งประเทศ

“ดังนั้น การเล่าเรื่องของนิทรรศการนี้ คือการเสนอสองมุมมอง แล้วให้คนชั่งน้ำหนักและความสมดุล” พิชัยเผยความตั้งใจในผลงานนิทรรศการครั้งใหม่ของเขา

In 2015, Thailand was notified by the European Union (EU) of the potential risk of being implicated in illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing. The EU issued a "yellow card", signalling a lack of cooperation, and warned that failure to address the issue could result in a "red card", leading to sanctions on Thai fishery exports.

At that time, the government—having come to power through a military coup—exerted considerable efforts to persuade the EU to lift the yellow card. This included the passing of laws that, in some instances, contravened fundamental legal principles, and the use of Section 44 as a means of expediting the implementation of these laws. These measures encompassed bans on certain fishing methods, such as trawl netting, regulations on both large and small fishing vessels, and even mandates requiring all vessels to secure permits before venturing to sea. While these policies impacted large-scale fishing enterprises, they disproportionately affected local fishermen, disrupting their livelihoods and cultural practices.

By 2019, after nearly four years of relentless lobbying, the government’s persistence bore fruit, and the EU lifted the yellow card against Thailand’s fisheries. This victory was widely celebrated, regarded as one of the government’s most significant accomplishments.

However, the jubilation overshadowed the considerable suffering endured by local fishermen across more than 22 coastal provinces. In the interim, many of these fishermen had lost everything—abandoning livelihoods passed down through generations. Their boats, once indispensable tools of their trade, were left to rot. By the time the yellow card was lifted, these boats had ceased to sail the waters, having long been abandoned.

In 2021, Pichai Pongsasaovapark, a contemporary artist from Songkhla Province, visited his sister in Pattani Province and noticed a decline in her fishing equipment business. Items such as fishing nets remained unsold, as they had been classified as illegal under the Fisheries Act B.E. 2558. This prompted Pongsasaovapark to investigate the impact of these regulations on the fishing industry in Pattani Province. The more he uncovered, the more he realised that the decommissioned fishing boats were being repurposed as scrap wood.

“What struck me as odd was the transformation of the boats. They were no longer boats, but scraps of wood. I decided that I had to see the site where these boats were being destroyed. When I visited Bana Subdistrict in Pattani Province, I was struck by the sheer volume of boat wreckage. We wondered why they had no place to store the remnants and why they had chosen this method of disposal. Where did these materials go once destroyed? This was the moment that ignited my curiosity,” Pongsasaovapark recalled.

Pongsasaovapark travelled extensively across various coastal communities in Pattani Province, building trust and rapport with the locals, who communicated in the Yawi language. Through interviews with villagers involved in the fishing industry, he learned that the story of a fishing boat extended beyond the fishermen themselves. He spoke with boat builders, boat painters, and even Kolae boat pattern painters, each of whom had been profoundly affected by the regulations.

“There’s no work now. My trade has vanished. I never had a moment of respite from building boats, but now there is no demand,” some of the words Pongsasaovapark heard from the community. He realised that, beyond the loss of occupation, these sentiments conveyed a deeper, more profound issue. For instance, Kolae boat painters, who had inherited their craft from previous generations, found themselves severed from their family legacy.

The first field visit provided some initial insights, guiding the second phase of Pongsasaovapark’s research, where he focused on identifying the groups of fishermen most affected and the core narrative he wished to convey. The answer, he found, lay with the commercial fishermen, whose boats were among the first to be destroyed.

Pongsasaovapark listened to the stories of over ten families, including both husbands and wives, and mothers and children. As the boats that sustained their livelihoods were abandoned and rendered obsolete, they were sold as scrap wood. Pongsasaovapark ventured to Bana Subdistrict and discovered a boat graveyard, where once-magnificent boats had been reduced to fragments of wood. Some of these fragments were repurposed as firewood for boiling anchovies, an ingredient used in the production of Budu sauce, a renowned local delicacy.

“When I visited the field, I found that the boat scraps were being distributed to different villages. The destruction of the boats in Bana Subdistrict was a catalyst for this process. What was striking was that the entire cycle occurred in the same location. Abandoned boats were destroyed and turned into scrap wood, which was then distributed to the villagers to be used as firewood for boiling anchovies, which in turn was used to make Budu sauce—a staple of the local cuisine.”

The more Pongsasaovapark engaged with the fishermen, the more he felt a profound connection to their sense of loss. He realised that the boats were not mere objects to be sold at will; they were symbols of a way of life and spirit deeply embedded in the community.

“It’s clear that acquiring a boat and earning a livelihood is no simple task. Fishermen don’t just do this for a year or two before abandoning it; they have been doing it for generations. Some fishermen, with little formal education, serve as captains or crew members, but it is a way of life in that region,” Pongsasaovapark remarked.

During this period, Pongsasaovapark collaborated with Nim Niyomsin, a curator, to analyse the project’s content and ensure a balance between the perspectives of the villagers and the government, which had enforced the laws. The issue was complex, involving multiple stakeholders.

“When Pongsasaovapark embarked on this project, there were two perspectives to consider: field research and balance. Pongsasaovapark conducted interviews with the villagers, but we also sought to present a balanced narrative that included the government’s perspective, particularly those responsible for issuing the laws,” Niyomsin explained.

A pivotal moment in the project occurred when the team met with fisheries academics from the Department of Fisheries, whose insights enriched the project, offering perspectives from both sides. This collaboration made the project even more compelling.

“I recall that initially, there were several challenges. In addition to purchasing boats, there were numerous legal complexities that affected various parties. We soon realised that this would be a substantial project, given the fishing industry’s intricacies. We decided that this would be the first exhibition Pongsasaovapark had done on this subject. We knew we couldn’t encapsulate everything in one exhibition—it had to evolve,” the curator shared about the collaboration with the artist. This marked the first time they had worked together.

After more than three years of fieldwork, data collection, and design, "Net Loss" emerged as Pongsasaovapark’s solo exhibition, curated by Niyomsin, at SAC Gallery. Through this exhibition, Pongsasaovapark sought to narrate the devastating effects and losses suffered by local fishermen through his works, including photographs, paintings, and installations.

From the shores of Pattani Province to the urban art gallery, remnants of fishing boats have been transformed into artwork titled Boat Spirit—a grand installation that is the first piece encountered upon entering the exhibition space.

“The work is based on the information we gathered. We sought to stay as true to the original materials as possible,” the artist explains of Boat Spirit. “I want the audience to see the real image, with authentic materials from the actual site. In truth, it was challenging to remove these pieces from the area, as they are heavily regulated.”

On the back wall of Boat Spirit, there is a photograph titled The Value Between Humans and Trees. While this artwork was created two years ago, the artist believes that displaying both works together enhances the message and connects it to the environmental issues he has recently addressed.

“A boat is made from a tree. Without trees, there would be no boats. Humans exploit nature and derive benefits from it. However, once they have reaped the rewards, they often forget the value of nature, discarding it as if it were expendable,” Pongsasaovapark explained.

Upon entering the second exhibition room, visitors encounter restored versions of the destroyed boats. The sculptures Anusornnumchok 3 and Laphprasert depict miniature fishing boats. The backstory behind these pieces involves the use of ashes from the burned boat remnants, mixed with ground-up nuts and nails, symbolising the cycle of the boats being reshaped into their original form. The artist also names these pieces after the destroyed vessels, employing various materials to experiment with this transformation.

Simultaneously, the exhibition also explores the fate and evolving roles of 48 small boats, which were first dismantled into wood scraps and ultimately repurposed as firewood for boiling fish to make Budu sauce. This transformation is depicted in the installation artwork 48 Lost Boats, which consists of 48 glass bottles filled with Budu sauce, each labelled with a different boat’s name. Alongside this installation are paintings titled Thick Budu Sauce and Thin Budu Sauce, prompting the viewer to reflect on the true value and purpose of a boat.

“Fishermen hold the sea in great reverence. They care deeply for every aquatic creature they harvest and are acutely aware of what is destructive and what is beneficial to the environment. I believe that fishermen who have been in the industry for 20-30 years, since their ancestors’ time, do not destroy nature,” Pongsasaovapark shared. “This sincerity reflects their understanding that they are not people who harm nature. They know what is appropriate to harvest, ensuring they don’t take fish too early in their life cycle. However, there are some who, without knowledge of the law, continue destructive practices, such as using fine-meshed nets. But most of the fishermen we spoke to cherish their work. It is their way of life, their family, their home, and they love nature.”

Net Loss is an exhibition rich in complexity, layered with numerous perspectives and untold stories in each piece. Of course, no artist can fully convey all the tales they’ve heard or the research they’ve conducted in a single exhibition. This exhibition serves as a starting point to invite viewers to acknowledge the often-overlooked voices affected by policies meant to protect nature—policies that may not fully take into account the devastation inflicted upon the way of life for saltwater fishermen.

Simultaneously, the exhibition avoids a one-sided narrative. From another perspective, the state, propelled by the yellow card as a catalyst, could not remain passive and was compelled to enact laws to mitigate practices still detrimental to the environment, in order to avert a national crisis.

“The storytelling in this exhibition is intended to present both perspectives, allowing the audience to weigh and balance them,” Pongsasaovapark concluded, sharing his vision for this powerful new exhibition.

Tuesday - Saturday 11AM - 6PM

Close on Sunday, Monday and Pubilc Holidays

For more information: info@sac.gallery

092-455-6294 (Natruja)

092-669-2949 (Danish)

160/3 Sukhumvit 39, Klongton Nuea, Watthana, Bangkok 10110 THAILAND

This website uses cookies

This site uses cookies to help make it more useful to you. Please contact us to find out more about our Cookie Policy.

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied in accordance with our privacy policy (available on request). You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.