OPEN HOURS:

Tuesday - Saturday 11AM - 6PM

Close on Sunday, Monday and Pubilc Holidays

For more information: info@sac.gallery

(English is below)

ไม่ว่าจะเป็นสายน้ำที่ไหลหล่อเลี้ยงชีวิต หรือสายน้ำที่มาพร้อมภัยพิบัติ

ไม่ว่าจะเป็นแบบไหน “น้ำ” เหล่านี้ กำลังสื่อสารอะไรกับเรา-มนุษย์อยู่

หลายคนเปรียบ “แม่น้ำ” (Mother Water) เป็นสายเลือดหล่อเลี้ยงชีวิต หรือเป็นความศักดิ์สิทธิ์

แต่สำหรับ ไฉ่ คุน ลิน ศิลปินชาวไต้หวัน เขาเปรียบแม่น้ำเป็น “หอจดหมายเหตุแห่งความทรงจำ” ที่ระหว่างการพำนักในโครงการศิลปินพำนักที่เชียงใหม่ เขาได้บันทึกเสียงใต้น้ำ ตั้งแต่แม่น้ำเจ้าพระยา ไปจนถึงแม่น้ำปิงและอ่างแก้ว ที่ไม่เพียงแค่ติดตามจังหวะชีวิตของสายน้ำ แต่ยาวไปถึงสายสัมพันธ์ของคนในละแวก

“ผู้คนมักคิดว่า เสียงใต้น้ำส่วนใหญ่มีแค่ฟองอากาศ หรือเสียงเงียบ แต่จริงๆ แล้วมีหลายเสียงเกิดขึ้นภายใต้ผิวน้ำ ทั้งปลา เครื่องจักร แม้กระทั่งเสียงการจราจรจากเมืองที่ส่งผ่านแม่น้ำ เมื่อผมเงี่ยหูฟัง มันคล้ายกับเสียงกระซิบ เสียงที่ต่อเนื่อง เสียงที่เกิดขึ้นตลอดเวลา แม้ว่าเราจะไม่เคยได้ยินมันมาก่อนก็ตาม”

หลังจากเฝ้าฟังเสียงกระซิบจากแม่น้ำในประเทศไทย สามสายแม่น้ำได้ไหลมาบรรจบกัน กลายเป็นแม่น้ำสายใหม่ ณ เอส เอ ซี แกลเลอรี ในนิทรรศการ “แม่น้ำ” ซึ่งเสียงเหล่านี้ถูกถ่ายทอดเพื่อบอกเล่าความทรงจำของกระแสชีวิต ไม่เพียงผ่านเสียงเท่านั้น แต่ยังสะท้อนผ่านงานประติมากรรมเซรามิก จิตรกรรม และภาพพิมพ์ ที่แต่ละชิ้นเหมือนน้ำที่ก่อตัวเป็นรูปร่าง คลื่น เคลื่อนไหว และกระทบแสง เปิดมุมมองใหม่ให้ผู้ชมเห็นสายใยและรายละเอียดที่เราอาจไม่เคยสังเกตมาก่อน

“ผู้ชมมักถามผมเสมอว่า เสียงน้ำนี้เกิดจากอะไร เกิดอะไรขึ้นใต้ผืนน้ำ เป็นปลาชนิดไหน แต่ผมไม่ใช่นักวิทยาศาสตร์ ผมเป็นศิลปิน ดังนั้น ผมเลยเริ่มคิดว่าแทนที่จะมานั่งอธิบายทุกอย่าง อาจจะดีกว่าถ้าผมเปลี่ยนเสียงเหล่านี้ให้กลายเป็นประติมากรรม

“เหมือนนักดนตรีที่ไม่จำเป็นต้องได้ยินเสียงจริง แต่เพียงพวกเขาอ่านตัวโน้ตก็จะจินตนาการได้ว่าเสียงนี้มีลักษณะอย่างไร”

เขาอธิบายต่อว่า การทำงานในนิทรรศการครั้งนี้เหมือนกับการสร้างตัวอักษรใหม่ขึ้นมา ผ่านงานศิลปะรูปร่างต่างๆ ที่เพียงเขามองงานปั้นเซรามิก หรือภาพวาด ก็สามารถนึกถึงเสียงแม่น้ำ ที่เขาเปิดฟังระหว่างทำงานศิลปะได้

ด้วยความที่ คุน ลิน เป็นชาวไต้หวัน ดังนั้นภาษาจีน จึงมีอิทธิพลต่อความคิดเขาเป็นอย่างมาก เพราะอักษรจีนมีฐานมาจากรูปภาพ แม้ว่าไม่ได้ยินเสียงพูดก็สามารถเข้าใจความหมายได้ นี่จึงเป็นที่มาของการสร้างประติมากรรม เพื่อบอกเล่าเสียงของแม่น้ำผ่านรูปทรง คล้ายกับการสร้าง “ภาษาใหม่” หรือหากพูดให้ง่ายกว่านี้คือ “ภาษาแม่น้ำ”

ศิลปินชาวไต้หวันอธิบายต่อว่า แม่น้ำแต่ละสายต่างมีเรื่องราวของตัวเองให้บอกกล่าว จากการบันทึกเสียงแม่น้ำหลายพื้นที่ พบว่าลักษณะเสียงของแต่ละสายแตกต่างกันอย่างชัดเจน เช่น แม่น้ำในกรุงเทพฯ เต็มไปด้วยชีวิตชีวา ทั้งเรือขนส่ง เรือท่องเที่ยว และเสียงการจราจร จึงส่งผลให้ใต้น้ำคึกคักและวุ่นวาย ปลาไม่หนาแน่นนัก แต่ในพื้นที่ลึกและสงบ เช่น ชนบท กลับสามารถได้ยินแม้กระทั่งเสียงฟองอากาศ สิ่งมีชีวิตเล็กๆ รวมไปถึงจังหวะของน้ำที่นุ่มนวล และละเอียดอ่อนกว่า

หากขยายไปให้กว้างกว่านี้หน่อย แม่น้ำของไทยและไต้หวันก็แตกต่างกันมากเช่นกัน เนื่องจากคนไทยใช้ชีวิตใกล้ชิดกับน้ำ จึงทำให้แม่น้ำเต็มไปด้วยชีวิตชีวา ในขณะที่แม่น้ำไต้หวันมักถูกควบคุม ปิดกั้น หรือปรับรูปร่างโดยงานก่อสร้าง เสียงที่บันทึกจึงมีความแตกต่าง

จึงปฏิเสธไม่ได้ว่า “คน” ส่งผลกระทบโดยตรงต่อแม่น้ำและสิ่งมีชีวิตในนั้น คุน ลิน อธิบายต่อว่า ความลึกของน้ำก็มีผลต่อเสียงกระซิบที่แตกต่างกัน เครื่องมือบันทึกของเขามีสายยาว 10 เมตร ดังนั้น ในแต่ละที่เขาต้องบันทึกเสียงสามระดับ คือ 1 เมตร, 5 เมตร และ 10 เมตร ซึ่งแต่ละความลึกก็ให้เสียงและพลังที่แตกต่างกัน และสำหรับแม่น้ำแต่ละสาย เขาจำเป็นต้องนั่งบันทึก และฟังซ้ำหลายครั้งเพื่อเก็บรายละเอียดทั้งหมด

“ก่อนเริ่มงานทุกครั้ง ผมจะเริ่มด้วยการค้นคว้า ศึกษาประวัติแม่น้ำ สถาปัตยกรรมรอบๆ และความสัมพันธ์ระหว่างคนกับน้ำ โดยผมรวบรวมจัดข้อมูล เรื่องราวต่างๆ แล้วเริ่มพิมพ์ สเก็ตซ์ภาพ และวางแนวคิดสำหรับประติมากรรม ผมฟังเสียงน้ำแล้ววาดตามจังหวะท่าทาง จากนั้นก็จะสร้างรูปทรงด้วยท่อ PVC หรือเซรามิกจากแบบดังกล่าว”

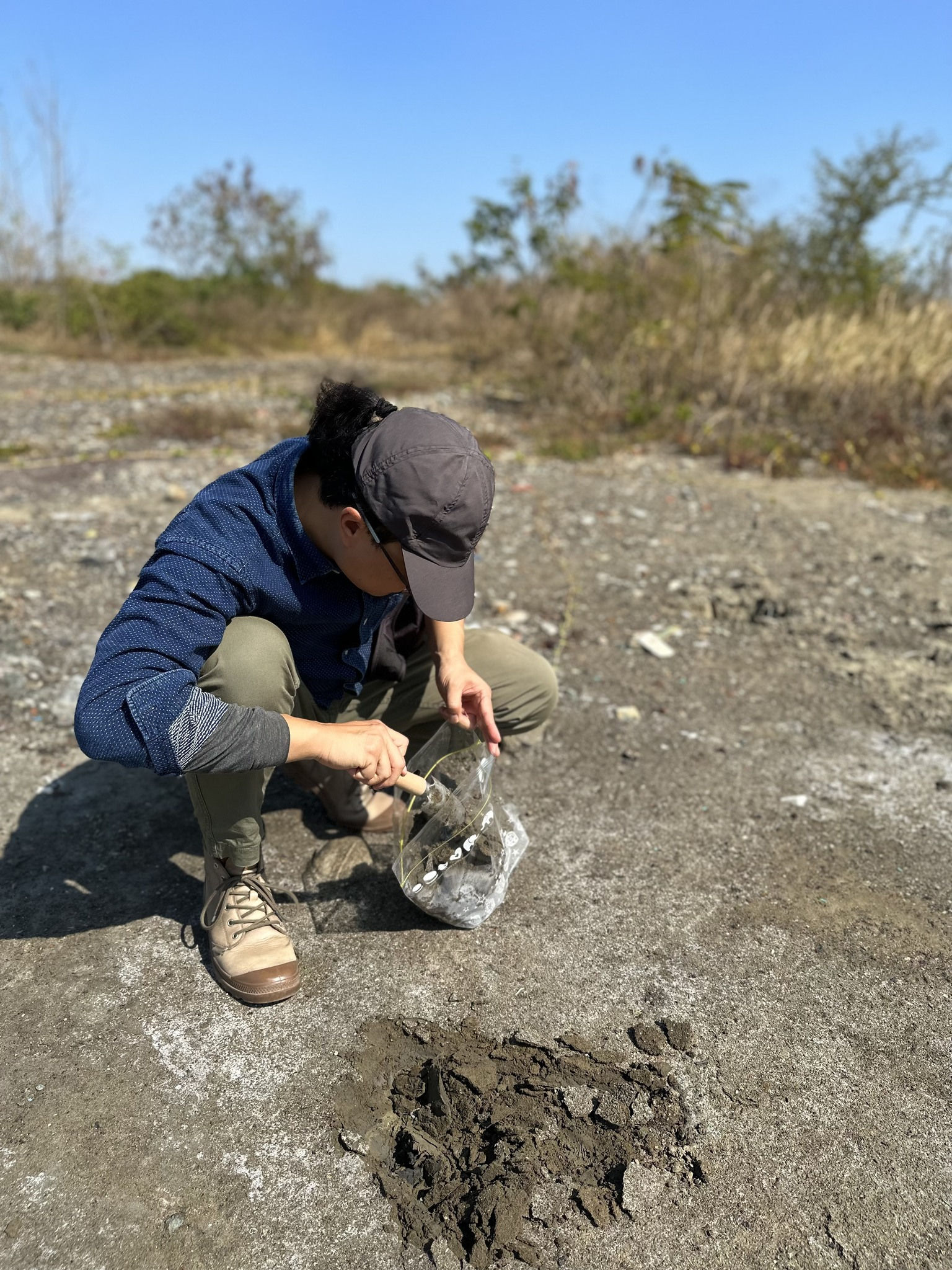

ในนิทรรศการครั้งนี้ คุน ลิน ได้เปลี่ยนจากท่อพีวีซีที่เคยใช้ในงานติดตั้งกลางแจ้ง มาสู่เซรามิกที่ปั้นจากดินซึ่งผ่านร่องรอยชีวิตของแม่น้ำที่เขาไปนั่งสดับรับฟัง

“ปีที่แล้วไต้หวันแล้งมาก แม่น้ำแห้งจนแทบไม่มีน้ำ ผมจึงเก็บดินที่แม่น้ำมาทำเซรามิก ผมรู้สึกว่าเซรามิกให้เสรีภาพมากกว่า ผมสามารถสร้างมุมได้เกิน 90° หรือ 45° ไม่ต้องถูกจำกัดอยู่ในสเปกท่อมาตรฐานจากโรงงาน”

ศิลปินชาวไต้หวันเล่าถึงจุดเริ่มต้นการเปลี่ยนจากท่อ PVC มาสู่การปั้นเซรามิก พร้อมอธิบายต่อว่าในกระบวนการทำงานศิลปะ เขาจะเริ่มต้นด้วยการฟังเสียงบันทึกใต้น้ำ และลงมือทำงานตามจังหวะพลิ้วไหลของสายน้ำ คล้ายกับศิลปินที่บรรเลงไปตามโน้ตดนตรี

“ดังนั้นกระบวนการทำงานศิลปะทั้งหมดของผมจะเน้นทำด้วยมือ ไม่มีสูตรตายตัว และเชื่อมทุกอย่างเข้าด้วยกัน”

หากใครได้มาเยือนนิทรรศการ “แม่น้ำ” และไม่รู้ว่าต้องเริ่มจากตรงไหน เพราะมีทั้งเสียงใต้น้ำ ประติมากรรมเซรามิก จิตรกรรม และภาพพิมพ์ คุน ลิน กล่าวว่า อยากให้ทุกคนสดับรับฟังแม่น้ำผ่านสายตาก่อน มองประติมากรรมหรือภาพพิมพ์ แล้วจินตนาการถึงเสียง แล้วถามตัวเองว่าอยากเห็นความงามแบบไหน อยากฟังเสียงแบบไหน แล้วหลังจากนั้นค่อยฟังเสียงกระซิบของแม่น้ำ

“ถ้าฟังเสียงก่อน จินตนาการจะถูกจำกัด เพราะเป็นเสียงที่ไม่คุ้นเคย แต่ถ้ามองก่อนแล้วฟัง ประสบการณ์จะเป็นส่วนตัวมากขึ้น คล้ายกับภาษาของตัวเอง”

เหตุผลที่ศิลปินชาวไต้หวันผู้นี้เปรียบแม่น้ำเป็น “หอจดหมายเหตุแห่งความทรงจำ” ก็เพราะเขาหมายถึงหอจดหมายเหตุของสายน้ำ ไม่ใช่ของมนุษย์

“เวลาบันทึกเสียง ผมจะเชื่อมโยงการค้นคว้า ทำความสัมพันธ์ระหว่างเสียงใต้น้ำกับเรื่องราว พร้อมกับเก็บความทรงจำ เก็บดิน บันทึกเสียงน้ำที่สะท้อนจากกิจกรรมของมนุษย์ มันไม่ใช่ความทรงจำของมนุษย์ แต่มันคือความทรงจำของธรรมชาติ”

แม่น้ำเป็นสิ่งที่ยิ่งใหญ่ สามารถเป็นทั้งผู้ให้และผู้ทวงคืน การบันทึกบทสนทนาใต้น้ำครั้งนี้จึงมากกว่าภาษาส่วนตัวของคุน ลิน แต่กลายเป็นหอจดหมายเหตุขนาดใหญ่ว่า ณ เวลานี้ แม่น้ำกำลังพูดและสื่อสารบางสิ่งบางอย่างกับมนุษย์และมวลมนุษยชาติอยู่

ดังที่ คุน ลิน เลือกคำมาอธิบายแม่น้ำเพียงคำเดียวว่า

“ผมเลือกคำว่า 'มี' เพราะแม่น้ำมีทุกสิ่ง มีชีวิต มีความทรงจำ และยังมีทุกสิ่งที่มนุษย์ทิ้งลงไป เราใช้ประโยชน์จากแม่น้ำหลายอย่าง และวันหนึ่งแม่น้ำก็จะเอาทุกสิ่งนั้นกลับคืนได้เช่นกัน”

Listening to Whispers Beneath the Water: What Is Nature’s Underwater Archive Telling Us?

Whether it is the water that sustains life or the water that arrives with disaster, whatever form it takes, what exactly is water trying to communicate to us as humans?

Many people describe a river or “Mother Water” as a life-giving bloodstream or a sacred force. For Taiwanese artist Tsai Kuen-Lin, however, a river is “an archive of memories”.

During his residency in Chiang Mai, he recorded underwater sounds from the Chao Phraya River, the Ping River and Ang Kaew Reservoir. These recordings do not simply followthe rhythm of the water but also extend into the lives of the communities who live alongside it.

“People often think underwater sounds are only bubbles or silence. In truth many things happen beneath the surface. Fish, machinery and even the traffic of the city can travel through the river. When I listen closely it feels like a whisper, a continuous presence that has always been there even though we have never truly heard it.”

After months of listening to these whispers from Thailand’s rivers, the sounds of three waterways come together to form a new river in his exhibition “Mae Nam” (River) at SAC Gallery. The underwater recordings appear with ceramic sculptures, paintings and prints. Each work resembles water taking form through shape, movement and glimmers of light that reveal details we may never have noticed before.

“Viewers often ask me what causes a certain sound or what is happening under the surface or what kind of fish they are hearing. I am not a scientist, I am an artist. Instead of explaining everything, I prefer to turn these sounds into sculptures.

“Just as musicians can imagine music simply by reading a score, I want people to imagine the sound through the form.”

Tsai explains that creating this exhibition feels like inventing a new set of characters, a language shaped through art. When he looks at the ceramic sculptures or paintings, he can recall the sound of the river he listened to while creating them.

Chinese characters have influenced his thinking since childhood because they originate from images. Meaning can be understood even without sound. This became the basis for creating sculptures that express river sounds through form, almost like developing a new language or what he calls a “river language”.

He discovered that every river carries its own story. His field recordings show that each river has a distinct sonic character. Rivers in Bangkok are full of activity with cargo boats, tourist boats and constant traffic so the underwater world feels busy and restless with fewer fish.

In deeper and quieter rural areas he could hear bubbles, tiny living organisms and gentle, delicate movements of water.

Thai and Taiwanese rivers differ for many reasons. Thais live closely with water which creates lively rivers. Taiwanese rivers are often controlled, enclosed or reshaped by construction which changes their sound. Human activity clearly affects the river and its living creatures.

Tsai also found that depth changes the water’s whisper. His recorder has a ten metre cable so he records at three levels, one, five and ten metres. Each depth produces a different resonance and energy. For every river he returns repeatedly to listen until he captures all its details.

“Before beginning any work I start by researching the river, its history, the architecture surrounding it and how people live with water. I collect stories then begin printing, sketching and shaping ideas. I listen to the water and draw according to its rhythm. From those sketches I create forms using PVC pipes or ceramics.”

For this exhibition he shifted from outdoor PVC installations to ceramics made from clay taken from the riverbeds where he listened.

“Last year Taiwan experienced a severe drought. Rivers dried up so I collected clay from the riverbeds to make ceramics. Ceramics give me more freedom. I can create angles that are not restricted by factory-made pipes.”

Throughout his process he listens to the underwater recordings while working, allowing the movement of water to guide his hands much like a musician responding to musical notes.

“The entire process is handmade. There is no set formula and everything is connected through sound.”

For visitors who may not know where to begin with the underwater audio, ceramic sculptures, paintings and prints he suggests beginning with sight.

“Look first. Let the sculptures or prints guide your imagination. Ask yourself what kind of beauty you sense, what kind of sound you imagine. Then listen to the river’s whisper.

“If you listen first your imagination becomes limited because underwater sounds are unfamiliar. If you look first and then listen the experience becomes more personal, almost like your own language.”

He calls rivers “archives of memory” because he is referring to the memories of water rather than those of humans.

“When I record I connect my research, the stories I gather, the soil I collect and the reflections of human activity. These memories do not belong to people. They belong to nature.”

Rivers are powerful. They give and they reclaim.

These underwater conversations become more than Tsai’s personal language. They form an archive of what rivers are saying to us today.

As he expresses in one simple word:

“I choose the word ‘have’ because rivers have everything. They have life and they have memory, and they hold everything humans leave behind.

“We take so much from rivers, and one day the river can take everything back.”

Tuesday - Saturday 11AM - 6PM

Close on Sunday, Monday and Pubilc Holidays

For more information: info@sac.gallery

092-455-6294 (Natruja)

092-669-2949 (Danish)

160/3 Sukhumvit 39, Klongton Nuea, Watthana, Bangkok 10110 THAILAND

This website uses cookies

This site uses cookies to help make it more useful to you. Please contact us to find out more about our Cookie Policy.

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied in accordance with our privacy policy (available on request). You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.