OPEN HOURS:

Tuesday - Saturday 11AM - 6PM

Close on Sunday, Monday and Pubilc Holidays

For more information: info@sac.gallery

(English is below)

“อวน” เป็นจุดเริ่มต้นของงานนิทรรศการนี้ ในเดือนเมษายน พ.ศ. 2564 พิชัย พงศาเสาวภาคย์ ได้มีโอกาสไปเยี่ยมพี่สาวที่จังหวัดปัตตานี พี่สาวของเขาทำธุรกิจขายเครื่องมือประมง ซึ่งเป็นธุรกิจอันเป็นส่วนหนึ่งของอุตสาหกรรมสำคัญที่สุดของจังหวัด ในการมาครั้งนี้ เขาสังเกตเห็นอวนจำนวนมากที่ยังคงไม่ได้ถูกจำหน่ายออกไป

อวนเหล่านี้ถูกจัดว่าเป็นอุปกรณ์ประมงผิดกฎหมาย ตามพระราชกำหนดการประมง พ.ศ. 2558 ซึ่งเป็นความพยายามของรัฐบาลในการจัดระเบียบอุตสาหกรรมประมงให้เป็นไปตามมาตรฐานสากล เพื่อให้ประเทศไทยพ้นจากสถานะใบเหลืองจากสหภาพยุโรป (EU) ในเรื่องของการประมงผิดกฎหมาย ขาดการรายงาน และไร้การควบคุม (IUU Fishing)

การออกและปรับปรุงกฎหมายดังกล่าวส่งผลกระทบต่ออุตสาหกรรมประมงเชิงพาณิชย์อย่างมาก โดยเฉพาะในกลุ่มผู้ประกอบการขนาดเล็กและท้องถิ่น หลายรายต้องหยุดดำเนินการกิจการและสูญเสียรายได้ จนเกิดการชะงักงันครั้งใหญ่ในภาคการประมง

ที่จังหวัดปัตตานี เรือประมงหลายลำต้องถูกจอดทิ้งไว้ เนื่องจากขาดเอกสารที่จำเป็นในการออกเรือ เพื่อบรรเทาผลกระทบนี้ รัฐบาลได้เสนอแผนการซื้อเรือจากผู้ประกอบการเพื่อนำออกจากระบบ โดยเรือส่วนใหญ่ที่ซื้อจะถูกทำลาย และซากเรือจะถูกนำไปจำหน่ายให้กับชาวบ้านซึ่งบางครั้งใช้เป็นเชื้อเพลิง จุดจบของวงจรชีวิตของเรือลำนั้นๆ

พิชัยตระหนักถึงความซับซ้อนของประเด็นในอุตสาหกรรมประมงที่ไม่สามารถสะท้อนได้ทั้งหมด เขาจึงเลือกที่จะใช้สถานการณ์นี้เป็นกรณีศึกษา โดยลงพื้นที่ที่ตำบลบานา อำเภอเมืองฯ จังหวัดปัตตานี หนึ่งในสถานที่นำร่องของโครงการนี้

ผลงานบางชิ้นในนิทรรศการนี้ได้รับแรงบันดาลใจจากวัสดุโดยตรง ในขณะที่ผลงานอื่นสะท้อนประเด็นที่เกี่ยวข้อง “อนุสรณ์นำโชค 3” และ “ลาภประเสริฐ” เป็นผลงานประติมากรรมที่สร้างขึ้นจากเศษซากเรือที่ถูกทำลายที่ตำบลบานา วัสดุชุดแรกที่ใช้ ได้แก่ ขี้เถ้าจากเศษไม้ที่ถูกเผาในกระบวนการทำน้ำบูดู ส่วนวัสดุชุดที่สอง เป็นการนำเศษโลหะ เช่น ตะปู น็อต และสกรู ซึ่งถูกบดเป็นผงเหล็ก ส่วนต้นแบบของประติมากรรมมาจากเรือ “อนุสรณ์นำโชค 3” และ “ลาภประเสริฐ” ที่ถูกทำลายเนื่องมาจากโครงการนี้

“แม่ย่านาง” เป็นผลงานที่ประกอบขึ้นจากเศษไม้ท่อนจากซากเรือ พร้อมการปิดทองที่สร้างความรู้สึกถึงขนาดและจิตวิญญาณของเรือจริง ผลงานนี้จัดแสดงคู่กับภาพถ่ายชื่อ “คุณค่าระหว่างมนุษย์และธรรมชาติ” ที่เป็นการตั้งคำถามถึงคุณค่าที่ถูกยึดถือในสิ่งต่างๆ

ผลงานชุด “น้ำบูดู” ประกอบด้วยจิตรกรรมสองชิ้น ชื่อว่า “บูดูน้ำข้น” และ “บูดูน้ำใส” รวมถึงงานจัดวางชื่อ “48 เรือที่สูญเสีย” โดยพิชัยได้ตามร่องรอยของเรือประมงไปจนถึงขั้นตอนการเผา หมายเลข 48 ในผลงานนี้แสดงแทนเรือ 48 ลำที่ถูกซื้อและทำลายในพื้นที่ เรือเหล่านี้สุดท้ายแล้วมีจุดหมายและประโยชน์ที่ต่างไปจากเดิมอย่างสิ้นเชิง ท้ายสุดแล้ว คำถามคือคุณค่าที่แท้จริงของเรือเหล่านี้คืออะไร

ผลงานสุดท้าย “ลูกข่างปลอม” เป็นงานที่สะท้อนถึงการตั้งคำถามเกี่ยวกับความจริง ศิลปินเลือกใช้วัสดุ Cubic Zirconia สีขาวที่มีลักษณะคล้ายเพชรจริง โดยเขาเลือกหยิบยืมการละเล่นพื้นบ้านไทยอย่างลูกข่าง โดยพิชัย มองและเปรียบเทียบการละเล่นนี้เป็นเหมือนนโยบายของรัฐที่อาจเปลี่ยนแปลงได้ ขึ้นอยู่กับผู้มีอำนาจ

นิทรรศการนี้มุ่งสำรวจแนวคิดที่ว่า ในหลายครั้งการที่มีบางคนสูญเสีย ขณะเดียวกันก็มีบางกลุ่มที่ได้รับประโยชน์ หลายคนตระหนักถึงปัญหาการประมงเกินขีดจำกัด (Overfishing) ที่ส่งผลกระทบต่อระบบนิเวศทางทะเล การควบคุมการประมงเพื่อความยั่งยืนจึงเป็นสิ่งจำเป็น ไม่เพียงเพื่อรักษาแหล่งอาหารแต่ยังเป็นการรักษาสิ่งแวดล้อม นอกจากนี้ การพัฒนาด้านสิทธิมนุษยชนของลูกเรือที่ได้รับการใส่ใจมากขึ้น และกลุ่มประมงพื้นบ้านก็ได้รับการส่งเสริมตามกฎหมายใหม่เช่นกัน โดยได้ประโยชน์จากการไม่ต้องแข่งขันกับเรืออวนลากขนาดใหญ่

แม้ทุกฝ่ายต่างเห็นพ้องเรื่องความจำเป็นในการปกป้องทรัพยากรทางทะเล แต่ยังมีข้อวิจารณ์เกี่ยวกับการกำหนดกฎหมาย ความเป็นไปได้ในการบังคับใช้ และมาตรการลงโทษ จังหวัดปัตตานีเป็นพื้นที่ที่มีช่องว่างระหว่างภาครัฐและประชาชนท้องถิ่น และแม้จะละเว้นการมองประเด็นทางสังคมและการเมือง ความซับซ้อนของปัญหานี้ก็ยังคงอยู่และเป็นเรื่องท้าทาย

หลังจากผ่านการปรับปรุง การสูญเสีย ประเทศไทยได้รับการยกเลิกใบเหลืองจากสหภาพยุโรปอย่างเป็นทางการในเดือนมกราคม พ.ศ. 2562 ซึ่งเป็นความโล่งใจสำหรับหลายฝ่าย อย่างไรก็ตาม แต่คำถามยังคงอยู่ ว่าแนวทางในอนาคต จะเป็นเช่นไร

นิทรรศการนี้นำเสนอเพียงบางส่วนของประเด็นที่ซับซ้อนเหล่านี้ โดยหวังว่าจะเป็นจุดเริ่มต้นในการศึกษาและทำความเข้าใจประเด็นดังกล่าวอย่างลึกซึ้ง ท้ายที่สุด สิ่งที่ทุกคนหวัง คือการสร้างสรรค์นโยบายและข้อบังคับที่ยุติธรรมและเป็นประโยชน์แก่ทุกฝ่าย

__________

Nets are the starting point of this exhibition. In April 2021, Pichai Pongsasaovapark had the opportunity to visit his sister in Pattani. Her business is in fishing supplies, a part of the fishing sector, the main industry of the province. During this visit, what caught his attention was a gigantic pile of unsold fishing nets.

These fishing nets were classified as destructive fishing gear, according to the Royal Ordinance on Fisheries (2015). This act was part of the Thai government’s efforts to regulate the fishing industry in order to lift the yellow card warning issued by the EU on Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) fishing. Commercial fisheries, especially small and local operators, were greatly affected by these new regulations. As a result, many people lost their businesses and sources of income. There was a major disruption within the industry.

In Pattani, many boats were left anchored by the shore. They were not permitted to operate as fishing boats due to issues with paperwork. In response, the government introduced a programme to buy back vessels. Once purchased, many of the boats were simply destroyed. Scraps were sold back to locals, who sometimes used them as firewood, marking the end of the vessel’s life cycle.

Recognising the impossibility of covering every complex issue surrounding the fishing industry, he saw this event as a compelling case study. His research took place in Tambon Bana, Muang District, Pattani. It was one of the pilot areas for the government programme to purchase unused fishing boats.

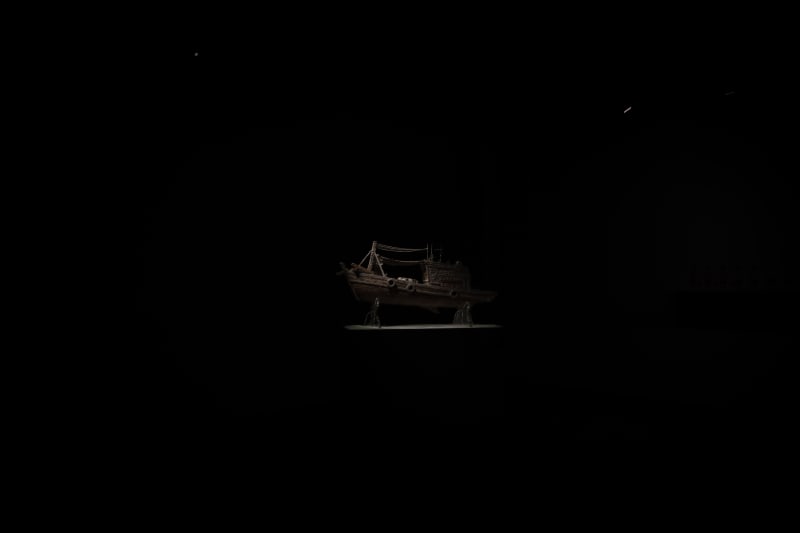

Some works in the exhibition were inspired by the materials, while others were shaped by the stories involved. Anusornnumchok 3 and Laphprasert were made from the byproducts of parts of destroyed fishing boats as a result of this program in Tambon Bana. Two primary materials were used. The first was ash from the burned wood of the discarded boat, which was used to boil big batches of anchovies in the production of Budu Sauce. The second was metal nails, knots and screws found at this site. They were ground and used as a material. The models were based on real fishing boats that had been destroyed, Anusornnumchok 3 and Laphprasert.

Boat Spirit presents a compilation of wooden parts collected from the site. The sheer scale of this piece, and the use of gold leaves, gives audiences a sense of the size and spirit of the real fishing boats. The work is displayed alongside Pongsasaovapark’s photography, The Value between Human and Trees. His photography questioned the value placed on living things and even objects.

The set of Budu Sauce-related works is comprised of two paintings, Thick Budu Sauce and Thin Budu Sauce, and an installation, 48 Lost Boats. Pongsasaovapark traces the final stage of the vessel’s life to Budu sauce production. The number 48 represents the fishing boats bought and destroyed in the studied area. The vessels were repurposed beyond their original function. In the end, the question of their ultimate value remains.

The final piece in the exhibition, Fake Spinning Top, stands apart from the others. This satirical work is made of white cubic zirconia to replicate a real diamond. It was inspired by a Spinning top, a Thai traditional game. Pongsasaovapark saw this game as a metaphor for government policies, which can shift and change direction depending on those in power.

This exhibition explores the idea that while there is a loss for some, there are often gains for others. For marine ecosystems, overfishing is a global issue. One of the solutions is to regulate the fishing industry to sustain the food chain and the environment. The human rights issues of ship workers had been improved. This regulatory shift also received positive feedback from artisanal fishers, who found themselves facing less competition from large, high-technology commercial boats within the coastal fishing areas.

No one disputes the urgency of protecting marine populations. The main issues and criticism revolved around how these regulations were formed, their practicality, enforcement, and punishment. Pattani has historically seen considerable gaps between central authorities and local populations. Even without considering social and political factors, the situation was already deeply problematic, complicated, and entangled.

After all these efforts, after much suffering and benefit, in January 2019, the EU officially lifted the yellow card status for Thailand. This provided relief, but the question remains: what will the future hold? This exhibition only touches on the surface of these complex issues, hoping to encourage deeper exploration. Ultimately, we hope those involved find fairness and solutions through future policies and regulations.

Tuesday - Saturday 11AM - 6PM

Close on Sunday, Monday and Pubilc Holidays

For more information: info@sac.gallery

092-455-6294 (Natruja)

092-669-2949 (Danish)

160/3 Sukhumvit 39, Klongton Nuea, Watthana, Bangkok 10110 THAILAND

This website uses cookies

This site uses cookies to help make it more useful to you. Please contact us to find out more about our Cookie Policy.

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied in accordance with our privacy policy (available on request). You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.